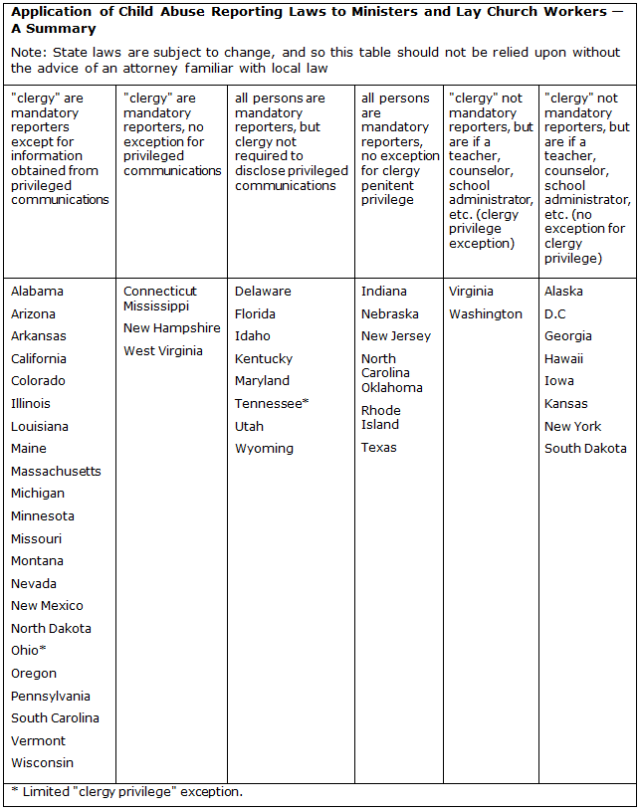

Key Point 4-08. Every state has a child abuse reporting law that requires persons designated as “mandatory reporters” to report known or reasonably suspected incidents of child abuse. Ministers are mandatory reporters in many states. Some states exempt ministers from reporting child abuse if they learned of the abuse in the course of a conversation protected by the clergy-penitent privilege. Ministers may face criminal and civil liability for failing to report child abuse.

Background

Every state has a child abuse reporting law that requires persons designated as “mandatory reporters” to report known or reasonably suspected incidents of child abuse. As Table 1 (see page 4) illustrates, ministers are mandatory reporters in many states, but some states exempt them from the reporting obligation if they learned of the abuse in the course of a conversation protected by the clergy-penitent privilege. This generally refers to confidential communications with a minister in the course of spiritual counsel.

Often, ministers do not report child abuse, either because they assume the clergy-penitent privilege applies and exempts them from reporting, or they want to resolve the matter internally through counseling with the victim or the offender without contacting civil authorities. Such a response can have serious legal consequences, including the following:

- ministers who are mandatory reporters under state law face possible criminal prosecution for failing to comply with their state’s child abuse reporting law;

- some state legislatures have enacted laws permitting child abuse victims to sue ministers for failing to report child abuse; and

- some courts have permitted child abuse victims to sue ministers for failing to report child abuse.

It is therefore imperative that ministers understand their child abuse reporting obligations under state law, and, in the case of mandatory reporters, report abuse unless they are certain that a valid exception, such as the clergy-penitent privilege, applies. If any doubt as to the availability of an exception exists, it is advisable to seek legal counsel. For example, the availability of the clergy-penitent privilege involves several legal issues, including:

- Am I a minister?

- Was the communication “confidential”?

- Was the communication made to me in my professional capacity as a spiritual advisor?

These often are complex issues that involve a thorough understanding of the underlying statute, and its interpretation by state and federal courts.

Table 1

Relevance to church leaders

This topic of child abuse reporting and the clergy-penitent privilege is relevant to church leaders for the following reasons:

Child abuse reporting and the clergy-penitent privilege

As noted in Table 1, ministers are exempted from a legal duty to report child abuse in some states if they learned of the abuse in a conversation protected by the clergy-penitent privilege. But, as the Louisiana Supreme Court concluded, not every communication with a minister is protected by this privilege. There are specific requirements that must be met. The communication must be in confidence; it must be made to a minister; and it must be made for the purpose of seeking spiritual counsel.

Clearly, not every conversation with a minister is privileged. Whether the privilege applies to a specific conversation is often a complex legal question involving familiarity with the privilege statute and court decisions interpreting it. As a result, ministers should never assume that they are exempt from a reporting obligation because of the application of the clergy-penitent privilege. This is a legal question for which legal counsel should be sought.

Who may claim the clergy-penitent privilege?

Rule 505 of the Uniform Rules of Evidence, which has been adopted by several states, specifies that “the privilege under this rule may be claimed by an individual or the individual’s guardian or conservator, or the individual’s personal representative if the individual is deceased. The individual who was the cleric at the time of the communication is presumed to have authority to claim the privilege but only on behalf of the communicant.” (emphasis added)

Many states permit the person who made the communication to prevent the minister or any other person from disclosing the communication. In some states, only the penitent or “counselee” may assert the privilege, not the minister.

Example. A member of a church informed three church officials that he had sexually molested a number of children. The mother of one of the victims sued the church, arguing that its negligence in not reporting the molester to civil authorities and in carelessly counseling with him had contributed to the molestation of her daughter. The molester later confessed to at least 33 acts of child molestation, and freely disclosed to the police the confessions that he had made earlier to the church officials. The mother sought to compel the church officials to testify regarding the confessions as part of her attempt to demonstrate that the officials had been aware of the risks posed by the molester and had been negligent in failing to report him to the authorities. This request was opposed by the church officials, who claimed that the confessions made to them were shielded from disclosure in court by the clergy-penitent privilege. The court ruled that under Arizona law the clergyman-penitent privilege “belongs to the communicant, not the recipient of a confidential communication,” and accordingly only the molester could assert it. The court rejected the church’s claim that the church officials to whom the confessions were made could independently assert the clergy-penitent privilege as a means of avoiding the obligation to testify. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints v. Superior Court, 764 P.2d 759 (Ariz. App. 1988).

Example. The Montana Supreme Court reversed a lower trial court’s $35 million judgment against a church, whose elders decided not to report allegations of sexual abuse by a step-father in the congregation. The court indicated the clergy-penitent privilege exception contained in the state’s abuse-reporting law applied to the church. The court concluded:

We hold accordingly that the undisputed material facts . . . demonstrate as a matter of law that [the church] was not a mandatory reporter [under state law] in this case because church doctrine, canon, or practice required that clergy keep reports of child abuse confidential, thus entitling the church to the reporting exception of the state child abuse reporting law. . . . Nunez v. Watchtower Bible & Tract Society, 2020 MT 3 (2019).

Many state laws give the minister the right to claim the privilege only on behalf of the penitent, meaning that if the penitent waives the privilege and agrees to testify, the minister cannot assert the privilege independently. This is the approach taken by Rule 505 of the Uniform Rules of Evidence. In other states, the minister can assert the privilege independently of the penitent.

Waiver of the privilege

The clergy-penitent privilege can be “waived” if a minister or counselee voluntarily discloses a privileged communication. Some courts have ruled that child abuse victims waive the privilege by voluntarily testifying in court concerning the content of their communications with their pastor.

Civil liability for failing to report abuse

In many states, clergy who are mandatory reporters, and who fail to report abuse, may be personally liable to victims of abuse assuming that no exception exists. This liability is based on either statute or judicial precedent.

liability based on statute

Eight states have enacted laws that create civil liability for failure to report child abuse. In these states victims of child abuse can sue adults who failed to report the abuse. Not only are adults who fail to report abuse subject to possible criminal liability (if they are mandatory reporters), but they also can be sued for money damages by the victims of abuse. In each state, the statute only permits victims of child abuse to sue mandatory reporters who failed to report the abuse. No liability is created for persons who are not mandatory reporters as defined by state law or whose mandatory reporter statusis negated by an exception. A summary of these eight state laws is set forth below. Note that in some states a minister’s mandatory reporter status may be negated by an exception(i.e., the clergy-penitent privilege).

1. Arkansas

Arkansas Code § 12-18-206 specifies that “a person required by this chapter to make a report of child maltreatment or suspected child maltreatment to the Child Abuse Hotline who purposely fails to do so is civilly liable for damages proximately caused by that failure.”

2. Colorado

Colorado Statutes § 19-3-304(4)(b) specifies that any person who is a mandatory reporter of child abuse and who willfully fails to report known or reasonably suspected incidents of abuse “shall be liable for damages proximately caused thereby.”

3. Iowa

Iowa Code § 232.75 specifies that “any person, official, agency or institution, required … to report a suspected case of child abuse who knowingly fails to do so or who knowingly interferes with the making of such a report … is civilly liable for the damages proximately caused by such failure or interference.”

4. Michigan

Michigan Compiled Laws § 722.633 specifies that “a person who is required by this act to report an instance of suspected child abuse or neglect and who fails to do so is civilly liable for the damages proximately caused by the failure.”

5. Montana

Montana Code § 41-3-207 specifies that “any person, official, or institution required by law to report known or suspected child abuse or neglect who fails to do so or who prevents another person from reasonably doing so is civilly liable for the damages proximately caused by such failure or prevention.”

6. New York

Section 420 of the New York Social Services Law specifies that “any person, official or institution required by this title to report a case of suspected child abuse or maltreatment who knowingly and willfully fails to do so shall be civilly liable for the damages proximately caused by such failure.”

7. Ohio

Section 2151.421(N) of the Ohio Revised Code: “Whoever violates division (A) of this section [i.e., mandatory child abuse reporters] is liable for compensatory and exemplary damages to the child who would have been the subject of the report that was not made. A person who brings a civil action or proceeding pursuant to this division against a person who is alleged to have violated division (A)(1) of this section may use in the action or proceeding reports of other incidents of known or suspected abuse or neglect, provided that any information in a report that would identify the child who is the subject of the report or the maker of the report, if the maker is not the defendant or an agent or employee of the defendant, has been redacted.”

8. Rhode Island

Section 40-11-6.1 of the Rhode Island General Laws specifies that “any person, official, physician, or institution who knowingly fails to perform any act required by this chapter or who knowingly prevents another person from performing a required act shall be civilly liable for the damages proximately caused by that failure.”

Persons who are mandatory child abuse reporters in Arkansas, Colorado, Iowa, Michigan, Montana, New York, and Rhode Island can be sued by victims of child abuse for failure to comply with state child abuse reporting requirements. These lawsuits may be brought in some states many years after the failure to report. It is possible that other state legislatures will enact laws giving victims of child abuse the legal right to sue mandatory reporters who failed to comply with their reporting obligations. It is also possible that the courts in some states will allow victims to sue mandatory reporters (and perhaps those who are not mandatory reporters) for failing to report child abuse even if no state law grants them the specific right to do so. These potential risks must be considered when evaluating whether or not to report known or suspected incidents of child abuse.

Key Point. Any reference to a specific state law should not be relied upon without the advice of an attorney. These laws were current as of the date of publication of this report, but they are subject to change. Also, it is important to understand the definition of child abuse under state law. A mandatory reporter has a duty to report only those activities (or suspected activities) that meet the definition of abuse under state law. The definition of child abuse varies widely from state to state. For example, in some states child abuse is limited to abuse inflicted by a parent or caretaker. Other states define abuse without regard to the status of the perpetrator.

liability based on court rulings

Several courts have refused to allow child abuse victims to sue ministers on the basis of a failure to comply with a child abuse reporting law. A few courts have reached the opposite conclusion.

(1) liability recognized

A few courts have ruled that clergy who are mandatory child abuse reporters under state law can be personally liable for monetary damages for failing to report abuse.

Example. An Indiana appeals court ruled that an adult who had been abused as a minor could sue his pastor on the basis of negligence for failing to report the abuse.

The court concluded:

[The pastor] knew of the alleged abuse and could have reasonably foreseen that it would continue absent adult intervention. In addition, there is a genuine issue of material fact as to whether [he] enjoyed a special relationship with [the victim]. When the level of interaction or dependency between an abused child and an adult results in a special relationship, the adult necessarily assumes a greater responsibility for that child. The special relationship imbues to the child a sense of security and trust. For the child, the stakes are high. For the adult, making a good faith report to a local child protection service is neither burdensome nor risky. In such circumstances, the adult is committing an even greater disservice to the child when the adult fails to make a report of the alleged abuse. J.A.W. v. Roberts, 627 N.E.2d 802 (Ind. App. 5 Dist. 1994).

Example. The Maine Supreme Court ruled that a religious organization could be sued by a victim of child molestation on the ground that it knew of the molestation but failed to report it to civil authorities. The court concluded, “If a religious organization knows or has reason to know that a member of its clergy has a propensity to sexually abuse children, the First Amendment is not necessarily violated if the civil law imposes on the organization a duty to exercise due care to protect children with whom the organization has a fiduciary relationship…. [The victim’s] claim that the diocese learned of the priest’s propensity to sexually exploit and abuse young boys, but failed to report him to law enforcement officials and then concealed the information from the parishioners, and the public, stated a claim upon which relief can be granted.” Fortin v. Roman Catholic Bishop of Portland, 871 A.2d 1208 (Me. 2005).

A few courts have ruled that mandatory reporters other than clergy are subject to civil liability for failing to report child abuse. But other courts have declined to impose civil liability on mandatory reporters for failing to report without a statutory basis.

Some courts have ruled that the legal doctrine of “negligence per se” applies to child abuse reporting statutes. This doctrine creates a presumption of negligence for violations of a statutory duty. As a result, mandatory reporters who fail to comply with their state’s child abuse reporting statute are presumed to have been negligent without any further proof. And, this is so even if the child abuse reporting statute does not explicitly state that mandatory reporters who fail to report abuse are subject to civil liability.

Example. A federal court in Pennsylvania ruled that a local church and denominational agency could be sued on the basis of the legal principle of “negligence per se” by a victim of child abuse as a result of their failure to report the abuse. Under the principle of negligence per se, a person who violates a statute can be sued for monetary damages if (1) the purpose of the statute is to protect the interest of the plaintiff, individually, as opposed to the public; (2) the statute must clearly apply to the conduct of the defendant; (3) the defendant must violate the statute; and (4) the violation of the statute must cause the plaintiff’s injury.

The court concluded that the church defendants were liable on this basis for their failure to comply with a state child abuse reporting statute. The significance of a finding of negligence per se is that actual negligence is presumed. There is no need to show any culpability on a defendant’s part other than a violation of the underlying statute. This means that a mandatory child abuse reporter’s failure to comply with a state child abuse reporting law’s requirement to report a known or reasonably suspected incident of child abuse would render that person automatically liable for monetary damages without a need for the victim to prove actual negligence. In other words, the mere failure to comply with the reporting requirement constitutes negligence per se. This sweeping conclusion has not been reached by any other court. Doe v. Liberatore, 478 F.Supp.2d 742 (M.D. Pa. 2007).

(2) liability rejected

Some courts have rejected the Louisiana Supreme Court’s conclusion that clergy who are mandatory child abuse reporters under state law may be personally liable for failing to report abuse. These courts have concluded that clergy and others who are mandatory child abuse reporters cannot be subject to civil liability for failing to report abuse unless the child abuse reporting law specifically creates this basis of liability.

Example. The Iowa Supreme Court ruled that a priest was not legally responsible for damages suffered by a victim of child abuse as a result of his decision not to report the abuse to civil authorities. A child (the victim) and her parents met with their parish priest on a number of occasions for family counseling. The priest was not a licensed counselor. The victim did not tell the priest that her father had sexually abused her but did tell him that he had “hurt” her. The physical and sexual abuse of the victim stopped when her father left home when she was in eighth grade. The victim attempted suicide a month later. The victim later sued her former priest and church. She claimed that the priest failed to report her abuse to the civil authorities, and that as a result the abuse continued, and her injuries were aggravated. She conceded that the priest was not aware that abuse had occurred, but she insisted that he should have been aware of the abuse based on her statement to him that her father had “hurt her.” A trial court dismissed the claim against the priest on the ground that he was not a mandatory child abuse reporter under state law and as a result had no duty to report the abuse even if he suspected it. The state supreme court affirmed the trial court’s decision. This case demonstrates that members of the clergy are not necessarily mandatory child abuse reporters under a state law that makes “counselors” mandatory reporters. Also, it illustrates that clergy who are not mandatory reporters, and who fail to report an incident of child abuse, will not necessarily be liable for the victim’s injuries. Wilson v. Darr, 553 N.W.2d 579 (Iowa 1996).

Example. The New Hampshire Supreme Court ruled that church leaders who failed to report allegations of child abuse could not be sued by the victims on the basis of their failure to report. The court conceded that the reporting law specifies that “any priest, minister, or rabbi or any other person having reason to suspect that a child has been abused or neglected shall report the same in accordance with this chapter.” However, the court concluded:

[The reporting law] did not give rise to a civil remedy for its violation. Failure to comply with the statute is a crime and anyone who knowingly violates any provision is guilty of a misdemeanor. The reporting statute does not, however, support a private right of action for its violation. Even assuming, without deciding, that the elders had an obligation to report suspected child abuse to law enforcement authorities, the plaintiffs have no cause of action for damages based on the elders’ failure to do so. Accordingly, we need not decide whether the church elders qualify as clergy for purposes of the religious privilege. Berry v. Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, 879 A.2d 1124 (N.H. 2005).

Example. A Mississippi court ruled that a school was not liable for the molestation of a minor student by a teacher as a result of its failure to comply with a child abuse reporting law. The court noted that the reporting duty only arose when a mandatory reporter had reasonable cause to suspect that abuse had occurred, and school officials did not have sufficient evidence of wrongdoing to have reasonable cause to suspect that the abuse had occurred. Further, the court noted that the reporting duty only applied to an “abused child,” and the victim in this case did not meet the statute’s definition of an abused child since she was not abused by someone “responsible for her care or support.” Doe ex rel. Brown v. Pontotoc County School District, 957 So.2d 410 (Miss. App. 2007).

Example. A Texas court ruled that ministers who are mandatory child abuse reporters under state law cannot be sued by child abuse victims on account of their failure to report. A 12-year-old boy was sexually molested by the children’s music director at his church. At first, the victim told no one. However, over the next few years the victim told five pastors in his church about the molestation. Although pastors are “mandatory reporters” of child abuse under Texas law, none of them reported the allegations to civil authorities or to the victim’s parents. The victim sued his church when he was an adult. He claimed that the church was responsible for his injuries because of its “inadequate response” to his “cries for help,” and because of the failure by the five pastors to report the abuse to civil authorities. The court concluded that the church was not liable for the victim’s injuries on account of the five pastors’ failure to comply with the state child abuse reporting law. The five pastors in this case were mandatory reporters under Texas law, and the victim claimed that their failure to report his allegations of abuse made them and the church legally responsible for his injuries. The court disagreed, noting that the state child abuse reporting law is a criminal statute and that “nothing in the statute indicates that it was intended to create a private cause of action.” Marshall v. First Baptist Church, 949 S.W.2d 504 (Tex. App. 1997).

Example. The Washington state supreme court ruled that an ordained minister could not be prosecuted criminally for failing to file a report despite his knowledge that a child was being abused. The minister was informed by a female counselee that her husband had sexually abused their minor child. The minister discussed the matter with both the husband and daughter in an attempt to reconcile the family, but filed no report with civil authorities within 48 hours, as required by state law. The minister was prosecuted and convicted for violating the state child abuse reporting statute. He received a deferred sentence coupled with one year’s probation and a $500 fine, and in addition was required to complete a “professional education program” addressing the ramifications of sexual abuse. The minister appealed his conviction, and the state supreme court reversed the conviction and ruled that the state child abuse reporting statute could not apply to clergy acting in their professional capacity as spiritual advisers.

The court noted that the state legislature’s 1975 amendment of the Washington child abuse reporting statute deleting a reference to “clergy” among the persons under a mandatory duty to report known or reasonably suspected cases of child abuse “relieved clerics from the reporting mandate. Logically, clergy would not have been removed from the reporting class if the legislature still intended to include them.” The court further observed:

Announcing a rule that requires clergy to report under all circumstances could serve to dissuade parishioners from acknowledging in consultation with their ministers the existence of abuse and seeking a solution to it …. [But] simply establishing one’s status as clergy is not enough to trigger the exemption in all circumstances. One must also be functioning in that capacity for the exemption to apply …. Thus we hold as a matter of statutory interpretation that members of the clergy counseling their parishioners in the religious context are not subject to the reporting requirement [under the state child abuse reporting law].

However, the court concluded that two “religious counselors” who were not ordained or licensed ministers could be prosecuted criminally for failure to report incidents of abuse that had been disclosed to them. The court concluded that the criminal conviction of the non-clergy “religious counselors” did not violate the first amendment guaranty of religious freedom. State v. Motherwell, 788 P.2d 1066 (Wash. 1990).

Example. A Washington state court ruled that the state child abuse reporting law did not give victims of abuse a right to sue a church for monetary damages as a result of a minister’s failure to report abuse, but victims in some cases may be able to sue a church on the basis of emotional distress as a result of how church leaders handled the case. The court quoted the trial judge:

If the jury finds that [the minister] basically discouraged the plaintiff from pursuing anything further because the family would break up, they’d be out on the streets, basically, everybody would be talking about her, if that’s true, then it seems to me that there’s plenty of room for a jury to find outrage, and that would be the basis of the outrage. This is a 13- or 14-year-old girl. This is sexual abuse. Someone who gets the courage up to go talk to an adult, a male adult at that, I believe that there’s plenty of evidence there for a jury to find that the tort of outrage was indeed committed if they believe that occurred. Doe v. Corporation, 167 P.3d 1193 (Wash. App. 2007).

Example. A federal court in Washington ruled that a mandatory child abuse reporter’s failure to report the abuse of a minor by a church worker could result not only in criminal liability for the reporter, but also civil liability for the reporter and his employing church. A minor (the “plaintiff”) who was sexually molested by a church worker sued the church, claiming that it was liable for the worker’s acts on the basis of its failure to comply with the state child abuse reporting statute. The church insisted that the state child abuse reporting law imposes criminal liability on mandatory reporters who fail to report abuse, but does not explicitly impose civil liability, and therefore the plaintiff could not sue the church for monetary damages in a civil lawsuit. The court disagreed.

It conceded that the reporting statute did not explicitly authorize civil lawsuits for failure to report, but ruled that such a right could be “implied” from the statute. It pointed to a Washington Supreme Court case that articulated three factors for the courts to consider in deciding if a statute creates a civil remedy: “First, whether the plaintiff is within the class for whose benefit the statute was enacted; second, whether legislative intent, explicitly or implicitly, supports creating or denying a remedy; and third, whether implying a remedy is consistent with the underlying purpose of the legislation.” The court concluded that these factors supported a finding that the state child abuse reporting law created a civil remedy in favor of abused minors and against mandatory reporters who fail to report abuse. Fleming v. Corporation of the President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, 2006 WL 753234 (W.D. Wash. 2006).

Example. A federal district court in Wisconsin ruled that a church was not legally responsible for the molestation of a young boy by a teacher at the church’s school. It rejected the victim’s claim that the church was responsible on the basis of a failure to report the abuse to civil authorities as required by state law. The court conceded that the school administrator had “reasonable cause to suspect” that one of his teachers had committed child sexual abuse and was obligated to alert the authorities under the state child abuse reporting law. However, the court emphasized that the church’s breach of its duty to report the suspected abuse to civil authorities could not have been the cause of the victim’s injuries since the victim could not prove that any of the acts of molestation occurred after the time a child abuse report should have been filed. Kendrick v. East Delavan Baptist Church, 886 F. Supp. 1465 (E.D. Wis. 1995).

Table 2

Civil Liability for Failing to Report Child Abuse

Note: Courts in the following states have refused to permit victims of child abuse to sue mandatory reporters who failed to report the abuse. Most of these cases are decisions by intermediate level appellate courts, meaning that the highest state court has not addressed the issue. Further, other intermediate level appellate courts in the same state may reach a different conclusion.

| Georgia |

• Reece v. Turner, 643 S.E.2d 814 (Ga. App. 2007). • Cechman v. Travis, 414 S.E.2d 282 (Ga. App. 1991). |

| Illinois |

• Doe ex rel. Doe v. White, 627 F.Supp.2d 905 (C.D. Ill. 2009) (noting that the child abuse reporting law “does not provide, expressly or impliedly, for a private right of action based on its violation”). • Cuyler v. United States, 362 F.3d 949 (7th Cir. 2004). |

| Iowa |

• Wilson v. Darr, 553 N.W.2d 579 (Iowa 1996). |

| Kansas |

• Kansas State Bank & Trust Co., v. Specialized Transportation Services, Inc., 819 P.2d 587 (Kan. 1991). |

| Maine |

• Fortin v. Roman Catholic Bishop of Portland, 871 A.2d 1208 (Me. 2005). |

| Minnesota |

• Becker v. Mayo Foundation, 737 N.W.2d 200 (Minn. 2007) |

| Mississippi |

• Doe ex rel. Brown v. Pontotoc County School District, 957 So.2d 410 (Miss. App. 2007). |

| Missouri |

• Bradley v. Ray, 904 S.W.2d 302, (Mo. App. 1995). |

| New Hampshire |

• Marquay v. Eno, 662 A.2d 272 (N.H. 1995). • Berry v. Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, 879 A.2d 1124 (N.H. 2005). |

| Pennsylvania |

• Morrison v. Diocese of Altoona-Johnstown, 2004 WL 3141330 (Pa. Com. Pl. 2004). |

| South Carolina |

• Doe ex rel. Doe v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 711 S.E.2d 908 (S.C. 2011) (“the legislature’s silence as to civil liability [in the child abuse reporting statute] indicated its intent not to create civil liability for failing to report as required”). • Doe v. Marion, 645 S.E.2d 245 (S.C. 2007) (“While [the child abuse reporting law] is silent as to civil liability [it does] impose liability for making a false report …. The fact that such language is missing … indicates the legislative intent was for the reporting statute not to create civil liability.”) |

| Texas |

• Marshall v. First Baptist Church, 949 S.W.2d 504 (Tex. App. 1997) (“nothing in the statute indicates that it was intended to create a private cause of action”). |

| Utah |

• Doe v. The Corporation of the President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, 98 P.3d 429 (Utah App. 2004) (“when a statute makes certain acts unlawful and provides criminal penalties for such acts, but does not specifically provide for a private right of action, we generally will not create such a private right of action”). |

| Washington |

• State v. Motherwell, 788 P.2d 1066 (Wash. 1990). • Doe v. Corporation, 167 P.3d 1193 (Wash. App. 2007) (a minister was not civilly liable for failing to report child abuse since he was not a mandatory reporter under state law). |

| West Virginia |

• Barbina v. Curry, 650 S.E.2d 140 (W.Va. 2007) (noting that the child abuse reporting law “does not give rise to an implied private civil cause of action, in addition to criminal penalties imposed by the statute, for failure to report suspected child abuse where an individual with a duty to report under the statute is alleged to have had reasonable cause to suspect that a child is being abused and has failed to report suspected abuse.”) |

| Wisconsin |

• Kendrick v. East Delavan Baptist Church, 886 F. Supp. 1465 (E.D. Wis. 1995). |

Key Point. Any questions regarding the application of child abuse reporting laws to ministers should be referred to an attorney for guidance and clarification.

Criminal liability for failing to report abuse

Persons who are mandatory reporters of child abuse under state law are subject to criminal prosecution for failure to report. Some clergy have been prosecuted for failing to file a report. Criminal penalties for failing to file a report vary, but they typically involve short prison sentences and small fines.

Example. A California appeals court upheld the conviction of two pastors for failing to report an incident of child abuse. The court rejected the pastors’ claim that their conviction amounted to a violation of the First Amendment guaranty of religious freedom by forcing them to report incidents of abuse rather than “handling problems within the church.” The court concluded:

The mere fact that a [minister’s] religious practice is burdened by a governmental program does not mean an exception accommodating that practice must be granted. The state may justify an inroad on religious liberty by showing it is the least restrictive means of achieving some compelling state interest. Here, if [the pastors] are held to be exempt from the mandatory requirements of the [child abuse reporting law] the act’s purpose would be severely undermined. There is no indication teachers and administrators of religious schools would voluntarily report known or suspected child abuse. Children in those schools would not be protected. The protection of all children cannot be achieved in any other way. People v. Hodges, 13 Cal. Rptr.2d 412 (Cal. Super. 1992).

As another example, in 2012, a Philadelphia jury convicted the “secretary for clergy” of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia of one count of child endangerment for allowing a priest to take a new position involving contact with minors after learning that he had had sexual contact with at least one other minor. The defendant received a prison sentence of three to six years. This case suggests that a mandatory reporter’s criminal liability for failing to report child abuse may extend beyond the misdemeanor liability imposed by the child abuse reporting statute and include potential felony liability. The priest’s conviction was reversed on appeal, but that ruling has been appealed to the state supreme court.