In a recent landmark ruling, a federal district court in Iowa addressed the potential liability of churches under the nondiscrimination provisions of a “public accommodations” law for failing to provide restroom and shower facilities according to a person’s “gender identity” as opposed to gender at birth. Fort Des Moines Church of Christ v. Jackson, 2016 WL 6089842 (S.D. Iowa 2016).

This article will review the facts of this case, explain the court’s ruling, and assess the possible significance of the case to churches and church leaders.

Background

A church in Des Moines, Iowa, claimed that state and municipal antidiscrimination laws unconstitutionally interfered with its constitutional rights. The church wanted to communicate messages that would place qualifications based on gender identity on who may use its restrooms and showers. It also wanted to explain its views supporting these qualifications through a sermon by one of its pastors. To these ends, it sought a preliminary injunction enjoining the enforcement of certain provisions of the Iowa Civil Rights Act (ICRA) and the Des Moines City Code, both of which prohibit places of public accommodation from discriminating based on gender identity. Both laws contain exemptions for religious acts of religious institutions. The members of the Iowa Civil Rights Commission (ICRC) and the state attorney general (collectively “the State Defendants”) and Defendant City of Des Moines (“the City”) asked the court to dismiss the church’s request for a preliminary injunction.

The church offers religious ministries, worship services, and other events and activities to its members and the public at large. It holds three weekly services, all open to the public. In addition, it regularly opens its facility to the public for weddings, funerals, and recreational and community activities, such as child care, a food pantry, and potluck dinners. The church asserted that even those activities that may not seem overtly religious are “religious in nature because they engender other important elements of religious meaning, expression, and purpose.” The church was emphatic that it does not wish to allow the use of its facility in any manner that is inconsistent with its religious mission and doctrine.

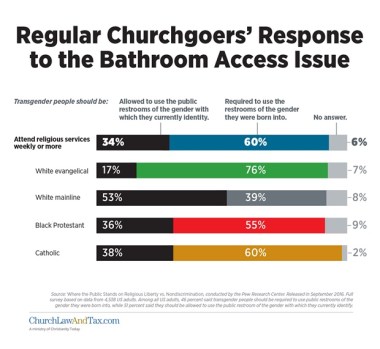

How regular churchgoers view the transgender bathroom access issue by denomination.

The church has two multioccupancy restrooms, each designated for the exclusive use of either males or females. Each restroom is equipped with a shower. The showers are located within the restrooms and they share an entrance. Additionally, the facility has two single-occupancy restrooms also designated for the separate use of each sex. The church views these designations as being limited to biological males or females. According to its beliefs, “sex” is an individual’s biological sex, determined at the time of birth by the individual’s anatomy, physiology, and chromosomes. The church has maintained an unwritten policy that areas designated for sex-specific use may only be used by members of that biological sex—a policy that comports with its religious teachings.

As a result of recent public attention given to gender identity and restroom access, the church decided that its policy should be clarified for its members and the public. Its leadership team adopted a written policy regarding the use of its facilities:

The church’s multiple occupancy bathrooms and the showers in the bathrooms are designated for single-sex use only. “Sex” is biological sex as determined by the physical condition of a person’s chromosomes and anatomy as identified at birth, or by one’s original birth certificate. This policy is consistent with and required by God’s Word, which sets forth the distinctiveness, complementariness and immutability of the male sex and female sex as Jesus Christ himself taught in Matthew 19:4. God’s Word also teaches that physical privacy and personal modesty spring from the physical conditions and unique characteristics of the sexes.

This bathroom and shower policy will be made available to members and the public by placing it on the church website and as an insert to the weekly worship bulletin that is distributed to all attendees of the Sunday worship service. We will also post this notice outside of our bathrooms within the building.

Despite the above language regarding its intent to distribute the policy, the church has not publicized or distributed the policy due to its belief that such publication and distribution would subject it to enforcement proceedings before the ICRC or the Des Moines Civil and Human Rights Commission pursuant to state and municipal antidiscrimination laws.

Several Iowa statutes and Des Moines ordinances were the focus of this lawsuit. In 2007, the Iowa legislature amended Iowa Code section 216.7 to bar places of public accommodation from discriminating against individuals on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. Iowa Code section 216.7 provides:

1. It shall be an unfair or discriminatory practice for any owner, lessee, sublessee, proprietor, manager, or superintendent of any public accommodation or any agent or employee thereof:

To refuse or deny to any person because of race, creed, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, religion, or disability the accommodations, advantages, facilities, services, or privileges thereof, or otherwise to discriminate against any person because of race, creed, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, religion, or disability in the furnishing of such accommodations, advantages, facilities, services, or privileges.

To directly or indirectly advertise or in any other manner indicate or publicize that the patronage of persons of any particular race, creed, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, religion, or disability is unwelcome, objectionable, not acceptable, or not solicited.

2. This section shall not apply to:

Any bona fide religious institution with respect to any qualifications the institution may impose based on religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity when such qualifications are related to a bona fide religious purpose (emphasis added).

Iowa Code section 216.2(13) defines a place of public accommodation as follows:

“Public accommodation” means each and every place, establishment, or facility of whatever kind, nature, or class that caters or offers services, facilities, or goods for a fee or charge to nonmembers of any organization or association utilizing the place, establishment, or facility, provided that any place, establishment, or facility that caters or offers services, facilities, or goods to the nonmembers gratuitously shall be deemed a public accommodation if the accommodation receives governmental support or subsidy. Public accommodation shall not mean any bona fide private club or other place, establishment, or facility which is by its nature distinctly private, except when such distinctly private place, establishment, or facility caters or offers services, facilities, or goods to the nonmembers for fee or charge or gratuitously, it shall be deemed a public accommodation during such period.

The ICRC released a brochure intended to serve as a guide to its interpretation of Iowa law with respect to civil rights issues concerning sexual orientation and gender identity. The brochure was titled Sexual Orientation & Gender Identity: A Public Accommodations Provider’s Guide to Iowa Law. In the original brochure, the ICRC posed the question “Does This Law Apply to Churches?” In response to that question, the ICRC posited the following:

Sometimes. Iowa law provides that these protections do not apply to religious institutions with respect to any religion-based qualifications when such qualifications are related to a bona fide religious purpose. Where qualifications are not related to a bona fide religious purpose, churches are still subject to the law’s provisions (e.g. a child care facility operated at a church or a church service open to the public).

Not long after the church filed its lawsuit seeking a preliminary injunction, the ICRC removed the original guide from its website and replaced it with a new one. The current version contains the subsection “Places of Worship,” which states:

Places of worship (e.g. churches, synagogues, mosques, etc.) are generally exempt from the Iowa law’s prohibition of discrimination, unless the place of worship engages in non-religious activities which are open to the public. For example, the law may apply to an independent day care or polling place located on the premises of the place of worship.

Both versions of the brochure contained a disclaimer: “This guidance document is designed for general educational purposes only and is not intended, nor should it be construed as or relied upon, as legal advice.”

The Des Moines City Code similarly forbids discrimination based on gender identity and other protected classes. Gender identity was added to the ordinance in 2011. Des Moines City Code section 62-136 provides:

It shall be an illegal discriminatory public accommodations practice for any person, owner, lessor, lessee, sublessee, proprietor, manager, superintendent, agent, or employee of any place of public accommodation to:

(1) Refuse or deny to any person because of race, religion, creed, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, ancestry or disability the accommodations, advantages, facilities, goods, services or privileges thereof or otherwise discriminate, separate, segregate or make a distinction against any person because of race, religion, creed, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, ancestry or disability in the furnishing of such accommodations, advantages, facilities, goods, services or privileges.

(2) Directly or indirectly print or circulate or cause to be printed or circulated any advertisement, statement, publication or use any form of application for entrance and membership which expresses, directly or indirectly, any limitation, specification or discrimination as to race, religion, creed, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, ancestry or disability or indicate or publicize that the patronage of persons of any particular race, religion, creed, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, ancestry or disability is unwelcome, objectionable, not acceptable or not solicited.

(3) Discriminate against any other person because such person has opposed any practice forbidden under this chapter or has filed a complaint, testified or assisted in any proceeding under this chapter.

(4) Aid, incite, compel, coerce, or participate in the doing of any act declared to be a discriminatory accommodations practice under this section, or attempt, directly or indirectly, to commit any act declared by this section to be a discriminatory practice.

Des Moines City Code section 62-1 defines a place of public accommodation to include any organization that “caters or offers goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, and accommodations to the public.”

Des Moines City Code section 62-137 states: “Nothing in this article shall be construed to apply to the following: (1) Any bona fide religious institution with respect to any qualifications the institutions may impose based on religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity, when such qualifications are related to a bona fide religious purpose.”

The lawsuit

Notwithstanding the religious exemption in both the state and municipal nondiscrimination laws, the church feared that it might qualify as a “public accommodation” through its gratuitous offer of services to the public at large. As a result, the church filed a lawsuit seeking a preliminary injunction barring enforcement of the public accommodations laws against the church. The church’s lawsuit alleged five causes of action.

- The nondiscrimination provisions in the state and local public accommodation laws are unconstitutional under the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.

- The nondiscrimination provisions in the state and local public accommodation laws are unconstitutional under the Religion Clauses of the First Amendment.

- The nondiscrimination provisions in the state and local public accommodation laws violate the church’s right to expressive association under the First Amendment.

- The nondiscrimination provisions in the state and local public accommodation laws violate the church’s right to peaceably assemble under the First Amendment.

- The nondiscrimination provisions in the state and local public accommodation laws are vague and violate the church’s right to Due Process under the Fourteenth Amendment.

The church attached to its lawsuit a sermon one of its pastors had written titled “A Biblical View of Human Sexuality.” The pastor provided a statement declaring that he had drafted the sermon but had declined to deliver it due to his fear of exposing the church to liability for violating Iowa law.

The court’s ruling

The court agreed with the defendants (the state of Iowa and city of Des Moines) that the church’s request for a preliminary injunction had to be dismissed on the ground that it lacked “standing” to prosecute its claims in federal court.

Standing is a requirement of any federal case, and derives from Article III of the United States Constitution that limits the jurisdiction of the federal courts to “cases and controversies.” To meet the “case or controversy” requirement, a plaintiff must establish “standing to sue” by showing that (1) he or she has been injured, and the injury is real rather than speculative or hypothetical; (2) the injury was caused by some action by the defendant; and (3) the injury would be “redressed” if the court grants the plaintiff the relief requested. If these conditions are not met, the dispute is not a “case or controversy” and the court is without constitutional authority to resolve it.

Injury in fact—sermons

The court noted that an injury must be “concrete and particularized or actual and imminent, rather than conjectural or hypothetical,” and that the purpose of this requirement “is to ensure that the alleged injury is not too speculative for Article III purposes.” Allegations of possible future injury “are not sufficient.”

The church claimed that it had been injured because:

(1) the state and city antidiscrimination laws forced it to refrain from posting its restroom policy out of a fear of prosecution or civil liability, and

(2) one of the church’s pastors claimed that he feared to deliver a sermon on sexual purity due to the possibility of exposing himself to liability.

By refraining to post these statements, or deliver the sermon, the church alleged that it had “self-censored” its speech.

The court acknowledged that “self-censorship may amount to an injury for purposes of standing if the plaintiff has been objectively reasonably chilled from exercising his First Amendment right to free expression in order to avoid enforcement consequences.” But, the court cautioned that “a plaintiff suffers from an objectively reasonable chilling of his First Amendment right to free expression by a criminal statute only if there exists a credible threat of prosecution under that statute if the plaintiff actually engages in the prohibited expression” (emphasis added). And, in order for a plaintiff to face “a credible threat of prosecution,” the allegedly threatened course of conduct must be prohibited by the challenged statute. The court concluded:

Plaintiff alleges that it fears prosecution under the state and municipal discrimination bans if it posts and distributes its facilities policy or if its pastor delivers his sermon about biological sex and the Bible. However, of these two alleged injuries, one—the delivery of the sermon—is based on a fear that is not objectively reasonable. All of the statutes, the ordinances, and the interpretations of the provisions appearing in the ICRC’s guidance documents include an exemption for religious institutions when conducting religious activities. Although the definitive scope of this exemption is yet to be determined, the court concludes the delivery of a sermon by a pastor of a church is undoubtedly an act intended to serve “a bona fide religious purpose.” Indeed, it is a quintessential religious activity. See Fowler v. State of R.I., 345 U.S. 67 (1953) … [in which the Supreme Court ruled] that it is not within “the competence of courts under our constitutional scheme to approve, disapprove, classify, regulate, or in any manner control sermons delivered at religious meetings,” and “sermons are as much a part of a religious service as prayers.” Hence, plaintiff’s allegedly chilled course of conduct is not even arguably proscribed by the statute. Rather, it is expressly permitted. Accordingly, plaintiff’s fear of enforcement consequences if it delivers the sermon is not objectively reasonable because it does not face a credible threat of prosecution on that basis … . A plaintiff cannot show a threat of prosecution under a statute if it clearly fails to cover his conduct.

In summary, the plaintiff lacked standing to challenge the constitutionality of applying the public accommodation laws’ nondiscrimination provisions to the content of sermons because sermons enjoy such broad and undisputed constitutional protection that it is inconceivable that the state or city would use these laws to punish churches based on the content of sermons. The court supported its conclusion by referring to a decision by the United States Supreme Court: “It is not within the competence of courts under our constitutional scheme to approve, disapprove, classify, regulate, or in any manner control sermons delivered at religious meetings,” and “sermons are as much a part of a religious service as prayers.” Fowler v. State of Rhode Island, 345 U.S. 67 (1953).

The court then turned its attention to the church’s restroom policy, which the church said it feared to publicize.

Injury in fact—posting the rest-room policy

The church argued that its decision not to post its restroom policy out of a fear of liability constituted additional injury satisfying the standing requirement. The court agreed:

The church pled that it provides services to the public gratuitously, which under certain circumstances could make it a place of public accommodation. It intends to make statements that may lead members of a protected class to feel that their patronage is unwelcome or not acceptable—at the very least, not accepted in the church’s restrooms or showers. Its proposed course of conduct is thus arguably proscribed by the statutes and ordinances at issue. Consequently, its fear of prosecution, which led it to self-censor its speech, is objectively reasonable. The court concludes the chilling of the church’s speech constitutes an injury in fact for the purposes of standing.

Injury caused by the defendant

To have standing to sue in federal court, a plaintiff not only must demonstrate an actual as opposed to a hypothetical injury, but also must be able to demonstrate that the injury was caused by the defendant. The court concluded that this requirement was met since “its injury is fairly traceable to challenged actions of the defendants.”

Redressability

To have standing to sue in federal court a plaintiff must also demonstrate that its injury would be redressed by a favorable ruling by the court. Once again, the court concluded that this element was met, and therefore the church had standing to pursue its claims in federal court.

The church’s motion for preliminary injunction

Having concluded that the church had standing to pursue its request for an injunction with regard to enforcement of the laws’ nondiscrimination provisions to the posting of its restroom policy, the court turned to the merits of the case. It began its analysis by observing that “a preliminary injunction is an extraordinary remedy never awarded as of right,” because it interferes with a defendant’s freedom of action. For the church to succeed in persuading a court to issue an injunction, it must establish a likelihood that it would succeed on the merits of the case in a court of law.

The church claimed that it would likely succeed in showing that the laws it was challenging are void under

- the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

- the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment, and

- the Free Exercise of Religion Clause and Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

The church claimed that the nondiscrimination provisions in the state and city public accommodations laws were void under the Due Process Clause on the basis of vagueness. The court conceded that a law is unconstitutionally vague if it “fails to provide a person of ordinary intelligence fair notice of what is prohibited, or is so standardless that it authorizes or encourages seriously discriminatory enforcement.”

The church pointed to several provisions in the state and city public accommodations laws that it regarded as vague. First, the church claimed that “bona fide religious institution” and “bona fide religious purpose” are impermissibly vague. But the court did not believe that “religious institution” or “religious purpose” is so subjective “that a reasonable person would realistically be unable to determine their meanings.” Further, the court did not believe that the term “bona fide” when placed alongside these terms rendered them overly vague, since it was reasonably clear that these words “conveyed the legislature’s intent to limit the religious institution exemption to those organizations who are genuine in their religious beliefs or those who request the protection of the religious institution exemption in good faith. Hence, the terms ‘bona fide religious institution’ and ‘bona fide religious purpose’ are not so subjective as to lead to seriously discriminatory enforcement.”

The court similarly rejected the church’s contention that other terms in the public accommodations laws were so vague as to be unconstitutional. The court conceded that some of these terms “do seem to leave room for a certain amount of subjectivity.” However, “considering them together within the context of the laws in question—laws aimed at preventing discrimination—the provisions are not so standardless as to lead to seriously discriminatory enforcement.”

The court concluded that it was not likely that the church would prevail in court on its vagueness challenge under the Due Process Clause.

Free Speech claim

The church claimed that the nondiscrimination provisions in the public accommodations laws violated its constitutional right of free speech under the First Amendment. The court disagreed, noting that “the problem with the church’s … challenge is that there is a significant amount of uncertainty surrounding whether the antidiscrimination laws would ever be applied to its conduct.” The court continued:

The burden is on the church to demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits of its … Free Speech claim, which includes explaining how the laws apply to it. The church pled that it holds many events that are open to the public; however, it stated that all of the events and activities it hosts, even those without “overt religious inculcation,” are intended to further its religious objectives. As a result, there are messages, practices, and activities that the church would not sponsor, host, or otherwise communicate because those messages, practices, and activities would violate the church’s understanding of God’s truth. [The state and city public accommodation laws] do not apply to “any bona fide religious institution with respect to any qualifications the institution may impose based on religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity when such qualifications are related to a bona fide religious purpose.”

The [brochure] drafted and circulated by the [state civil rights commission] gives at least some insight into what it believes are “non-religious activities” that could fall within the scope of the statute and which churches occasionally host. Such examples are “an independent daycare or a polling place.” This interpretation of the exemption would place the emphasis on who exercises control over a given event and for what purpose. The church has not pled that it ever allows events of a nonreligious nature that function independent from the church to be held within its facility. In fact, in its complaint the church repeatedly stated the opposite.

The court noted that other courts that have addressed the issue have concluded that churches and programs they host are not places of public accommodation, citing the following cases:

- Traggis v. St. Barbara’s Greek Orthodox Church, 851 F.2d 584 (2d Cir. 1988): Holding that a church had not violated Connecticut’s civil rights act because it was not a public accommodation.

- Vargas-Santana v. Boy Scouts of America, 2007 WL 995002 (D.P.R. 2007): “As a matter of law, a church is not a place of public accommodation.”

- Saillant v. City of Greenwood, 2003 WL 24032987 (S.D. Ind. 2003): Holding that a church could exclude persons of its choosing from its property because a “church is not a place of public accommodation.”

- Wazeerud-Din v. Goodwill Home & Missions, Inc., 737 A.2d 683 (N.J. App. 1999): Holding that a church’s addiction program was not a public accommodation under the New Jersey “Law Against Discrimination” (LAD); the group was essentially religious in nature in that it devoted time to the study of Christian tenets and “a religious institution’s solicitation of participation in its religious activities is generally limited to persons who are adherents of the faith or at least receptive to its beliefs.” The court concluded:

Although churches, seminaries and religious programs are not expressly excluded from the definition of “place of public accommodation,” the Legislature clearly did not intend to subject such facilities and activities to the LAD. None of the enumerated examples of “public accommodations” set forth in [the LAD] are similar in any respect to a place of worship or religious training.

Furthermore, a church or other religious institution does not ordinarily solicit the general public’s participation, which is “a principal characteristic of public accommodations.” Dale v. Boy Scouts of America, 734 A.2d 1196 (1999). Instead, a religious institution’s solicitation of participation in its religious activities is generally limited to persons who are adherents of the faith or at least receptive to its beliefs. The conclusion that religious facilities and activities are not public accommodations is also supported by the Division on Civil Rights’ long-standing position, as expressed in an affidavit which its former director submitted in connection with other litigation, that the LAD does not “regulate or control religious worship, beliefs, governance, practice or liturgical norms.” Moreover, any attempt to regulate a religious institution’s policies concerning participation in its religious activities would raise serious constitutional questions … . Consequently, in the absence of a clear expression of legislative intent to extend the coverage of the LAD into this domain, [the LAD] should be construed to avoid governmental entanglement with religion in order to preserve its constitutionality.

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 548 A.2d 328 (1988): Holding that parochial schools run by the Catholic church are not places of public accommodation under Pennsylvania law.

The Iowa federal district court noted at a pretrial hearing that the state and city defendants stated that the church’s restroom policy was likely permitted under the antidiscrimination laws “because the policy is plainly drafted to serve a religious purpose and that all of the activities the church enumerated within its complaint also appeared to be religious in nature.” The court noted that “such acknowledgements do not prevent the state and city defendants from seeking enforcement against the church and so assigns these statements little weight. However, in light of the previous determinations, they seem to be one more indication that the outcome of the church’s claim is far from certain.”

The court concluded:

On the current facts, the church has not shown that the challenged laws would ever apply to its conduct. Hence, its likelihood of success on the merits of its Free Speech challenge appears dim; there are too many obstacles it must overcome. The church may put forward a more compelling case for success on this claim at a later stage of this dispute—at present, it has not done so. The court concludes that the church has not shown the requisite likelihood of success on its Free Speech claim.

Free Exercise of Religion claim

Next, the court addressed whether the church was likely to succeed on its challenge to the constitutionality of the antidiscrimination laws on the basis of its right to freely exercise its religion. Under the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

The court noted that “the Free Exercise Clause clearly protects a citizen’s right to his or her own religious beliefs. [It] means, first and foremost, the right to believe and profess whatever religious doctrine one desires.” However, “the Free Exercise Clause does not shield every act that may be infected with religiosity from government regulation.” The United States Supreme Court has noted that “we have never held that an individual’s religious beliefs excuse him from compliance with an otherwise valid law prohibiting conduct that the State is free to regulate.” And, significantly, “a law that is neutral and of general applicability need not be justified by a compelling governmental interest even if the law has the incidental effect of burdening a particular religious practice.” In other words, the Free Exercise of Religion clause, as currently construed by the Supreme Court, recognizes “neutral laws of general applicability” as consistent with the Free Exercise Clause. Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520 (1993).

The Iowa court concluded that the state and municipal public accommodations laws in this case were neutral toward religion, and of general applicability, and therefore consistent with the Free Exercise of Religion Clause of the First Amendment.

Establishment Clause claim

The plaintiffs also claimed that the public accommodation laws under consideration violated the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, which states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion … .” The court failed to see how this clause was implicated or violated by the public accommodation laws in this case. Further, “the three main evils against which the Establishment Clause was intended to afford protection are sponsorship, financial support, and active involvement of the sovereign in religious activity,” none of which were implicated in this case.

As a result, the court concluded that the plaintiffs were “not likely to succeed on the merits of their challenges to the state and municipal antidiscrimination laws under either the Free Exercise Clause or the Establishment Clause,” or under the Constitution’s Free Speech or Due Process Clauses, and so their request for an injunction had to be denied.

Key point. The state and city defendants cautioned that the result in this case might have been different if the church “allowed the use of its facility as commercially available space with no religious limitations placed on such use.”

Relevance to churches

Historically, a person’s gender was determined at birth. But in recent years, some have argued that their “gender identity” is different from their gender at birth. For example, while born a male, a person comes to identify with the female gender. Such persons are commonly referred to as “transsexuals.” Some of them have surgery or hormonal therapy to change some of their physical characteristics, but many do not.

In recent years, “gender identity” has emerged as a legally protected status, usually as a result of a nondiscrimination provision in a state or municipal public accommodations law. This has caused considerable confusion and concern for many church leaders, and has raised a number of ethical, theological, and legal issues. For example, is a church legally required to:

- Allow persons to use restrooms according to their sexual identity even if different from their gender at birth?

- Allow transsexuals who have received surgical or hormonal treatments to alter certain sexual characteristics to use restrooms according to their gender identity?

- Allow persons to share hotel rooms on church-organized trips according to their gender identity rather than their gender at birth?

- Refrain from discriminating in employment decisions on the basis of gender identity?

The answers to these questions are complicated by two factors. First, few courts have addressed these issues, and second, any answers will depend on the terms in a veritable patchwork quilt of hundreds of local, state, and federal laws forbidding discrimination by places of “public accommodation.”

Application to Churches

The following analysis should enable church leaders to assess the potential application of the nondiscrimination provisions in a public accommodation law. Important questions to address are:

- Is the church a “place of public accommodation” under applicable local, state, or federal laws?

- What forms of discrimination are prohibited by places of public accommodation (i.e., is gender identity included)?

- If a state or local public accommodations law defines a “place of public accommodation” to include churches, or if a regulatory agency has done so, can the church assert a constitutional defense to coverage based on the First Amendment’s free exercise or nonestablishment of religion clauses?

- These questions are addressed below, in light of the Iowa court’s ruling and other precedent.

- 1. Is the church a “place of public accommodation” under applicable local, state, or federal laws?

- Obviously, the first question to resolve in investigating the application of a public accommodations law to a church is whether churches satisfy the definition of a “place of public accommodation” under the law. There are three possibilities:

- The law excludes churches from the definition of a “place of public accommodation.”

- Churches are excluded from the definition of a “place of public accommodation” but only if certain conditions are met. For example, a church does not rent its property to the general public for weddings and other events.

- Churches are included in the definition of a place of public accommodation even if they do not rent their property to the general public or engage in any other commercial activity. To illustrate, four churches challenged a Massachusetts law that was construed by the state attorney general to include “houses of worship” within the definition of a place of public accommodation regardless of rental or other commercial activity. The state attorney general later announced that “while religious facilities may qualify as places of public accommodation if they host a public, secular function, an unqualified reference to ‘houses of worship'” was inappropriate.

- The most likely basis for the legal protection of transgender persons on church property will be the nondiscrimination provisions in public accommodations laws. But these laws only apply to entities that meet the definition of a place of public accommodation. Whether churches are included in this definition will depend on the language in each public accommodations law. Set forth below are summaries of most of the court cases that have ever addressed this question. These are in addition to the five cases cited by the Iowa court concluding that churches are not necessarily places of public accommodation (see above).

- (1) Thomas v. County of Camden, 902 A.2d 327 (N.J. App. 2006)

- A New Jersey court provided a helpful analysis on the meaning of “public accommodation”:

Generally, in the context of private entities, from commercial to membership organizations providing services to the public, we have developed standards to help determine whether the entity qualifies as a public accommodation. In this regard, our “focus appropriately rests on whether the entity engages in broad public solicitation, whether it maintains close relationships with the government or other public accommodations, or whether it is similar to enumerated or other previously recognized public accommodations.” For non-public entities, the existence of broad public solicitation has consistently been a principal characteristic of public accommodations.

- (2) Sloan v. Community Christian School, 2015 WL 10437824 (M.D. Tenn. 2015)

- Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) protects individuals with disabilities from discrimination in public accommodations. Title III of the ADA provides that it shall not apply to religious organizations or entities controlled by religious organizations, including places of worship.

- A federal district court in Tennessee noted that “this exemption is very broad, encompassing a wide variety of situations. Even when a religious organization carries out activities that would otherwise make it a public accommodation, the religious organization is exempt from ADA coverage. Thus, if a church itself operates a day care center, a nursing home, a private school, or a diocesan school system, the operations of the center, home, school or schools would not be subject to the requirements of the ADA. The religious entity would not lose its exemption merely because the services provided were open to the general public. The test is whether the church or other religious organization operates the public accommodation, not which individuals receive the public accommodation’s services.”

- This case addressed the definition of “a place of public accommodation” under Title III of the ADA rather than a state or local public accommodations law. Nevertheless, its discussion of this key term provides some clarification, even if by inference. It suggests that churches that operate “a day care center, a nursing home, a private school, or a diocesan school system,” may be places of public accommodation subject to the nondiscrimination provisions of a local or state public accommodations law.

- (3) Doe v. Abington Friends School, 2007 WL 1489498 (E.D. Pa. 2007)

- In another case addressing the exemption of religious organizations from the public accommodations provisions of the ADA (see the previous case), a federal district court in Pennsylvania observed:

Although a religious organization or a religious entity that is controlled by a religious organization has no obligations under the rule, a public accommodation that is not itself a religious organization, but that operates a place of public accommodation in leased space on the property of a religious entity, which is not a place of worship, is subject to the rule’s requirements if it is not under control of a religious organization. When a church rents meeting space, which is not a place of worship, to a local community group or to a private, independent day care center, the ADA applies to the activities of the local community group and day care center if a lease exists and consideration is paid. 28 C.F.R. Pt. 36, App. B (2007).

- Most public accommodations laws contain an exemption for churches that do not invite the public onto their premises for events and activities unrelated to worship or the exercise of a church’s core purposes, but the exemption of other religious organizations, including those affiliated with a church, is less clear and varies from state to state.

- (4) Barker v. Our Lady of Mount Carmel School, 2016 WL 4571388 (D.N.J. 2016)

- A parent sued a church-operated elementary school in a New Jersey federal district court for discriminating against her children in violation of the nondiscrimination provisions of a state public accommodations law (the New Jersey Law Against Discrimination or NJLAD). The court noted that the NJLAD prohibits discrimination on various grounds in any “place of public accommodation,” a term that includes schools.

- However, the NJLAD does not apply to any educational facility operated or maintained “by a bona fide religious or sectarian institution,” and this exception “applies both to elementary and high schools operated by religious institutions under the supervision of the State Board of Education and to purely religious schools which are not subject to any form of governmental regulation.”

- The court concluded that the religious school exception applied in this case since the school was operated by its parent church and diocese. The court added that the church and diocese were also exempt from the nondiscrimination provisions of the NJLAD. It concluded: “Although churches, seminaries and religious programs are not expressly excluded from the definition of ‘place of public accommodation,’ the legislature clearly did not intend to subject such facilities and activities to the NJLAD.” Thus, the claims against these institutional defendants fail as a matter of law.

- (5) Presbytery of New Jersey v. Florio, 40 F.3d 1454 (3rd Cir. 1994) aff’d 99 F.3d 101 (1996)

- In April 1992, a minister, church, and regional denominational agency (the “plaintiffs”) sued the state of New Jersey in federal court to enjoin enforcement of recent amendments to a state law prohibiting several forms of discrimination by places of public accommodation. The amendments added “affectional or sexual orientation” to the personal characteristics generally protected against discrimination in public accommodations.

- The plaintiffs challenged these and other provisions as an infringement on the First Amendment right to the free exercise of religion and association as well as the right to freedom of speech. They sought a preliminary injunction prohibiting the state from enforcing these provisions against it. The federal district court denied the motion for a preliminary injunction holding that the plaintiffs failed to establish both a likelihood of success on the merits and irreparable harm. The plaintiffs appealed, and a federal appeals court affirmed the district court’s ruling. Because of the state’s affidavit stating its intention not to enforce the nondiscrimination law against religious institutions, the appeals court concluded that the plaintiffs failed to demonstrate the possibility of immediate and irreparable harm. The court also ruled that the possibility of private enforcement of the law by activist homosexual groups was too remote to constitute an immediate threat of potential harm and, in any event, the private parties would not be bound by the injunction sought.

- The state asked the federal district court to dismiss the plaintiff’s claims. The court granted the state’s motion and dismissed the case. It held that the case was premature based on the state’s affidavit that it would not enforce the law against the institutional plaintiffs as churches or the pastor in his capacity as a clergyman. Once again, the plaintiffs appealed.

- On appeal, the plaintiffs alleged:

- Based upon the Holy Bible and church doctrine, the church and parent denomination teach that homosexuality, bisexuality, and heterosexual sex outside of marriage are grievous sins.

- Plaintiffs also allege that they have always in the past, presently do and since the 1992 amendments, have directly or indirectly discriminated against and made reasonable distinctions based upon homosexuality, bisexuality and heterosexual sex outside of marriage. For example, in New Jersey the plaintiffs express, speak and preach against homosexuality, adultery and fornication, calling it variously an abomination and sinful. They also disseminate and circulate such speech and distinctions throughout New Jersey and the world. They even print and disseminate materials condemning sexual sins. Plaintiffs, and their members, also inquire about the sexual practices of prospective employees and are continuing to do so despite the existence of the 1992 amendments.

- The pastoral plaintiff and members of his congregation “speak out about homosexuality, bisexuality and heterosexual sex outside of marriage, make reasonable distinctions based on such practices, lobby against them, and circulate literature condemning them. They encourage, aid and abet discrimination and reasonable distinctions against homosexuals, bisexuals and heterosexuals engaging in sex outside of marriage.”

- The pastoral plaintiff and his church members “have always in the past, presently do and since the amendments have refused to knowingly buy from, contract with or otherwise do business with persons on the basis of that person’s homosexual, bisexual or heterosexual practices.”

- The pastoral plaintiff and his church members also “have always in the past, presently do and since the amendments have refused to employ any individual who is practicing any public sexual sin, including fornication, adultery and homosexuality, and they make reasonable distinctions based on such acts.”

- The director of the state division of civil rights (Gregory Stewart), filed an affidavit setting forth the position of the division and state attorney general regarding enforcement of the nondiscrimination provisions in the state public accommodations law against religious institutions. The “Stewart affidavit” affirmed that the state did not consider churches places of “public accommodations.” Thus, the sections relating to public accommodations were “inapplicable to the church plaintiffs.”

- Stewart further stated that churches were considered exempt in their hiring of employees. Due to “First Amendment concerns,” the division “has not in the past prosecuted and has no intention to prosecute essentially exempt churches for sincerely-held religious belief or practice, or speech consistent with such belief, or for a refusal to engage in certain speech or for following their religious tenets. Hence, the division would not even attempt to enforce those provisions in the circumstances of sincerely-held religious reasons such as plaintiffs express here.”

- Stewart also made the following general statement:

It has been the consistent construction and interpretation of the [law] that, consonant with constitutional legal barriers respecting legitimate belief and free exercise protected by the First Amendment, the state was not authorized to regulate or control religious worship, beliefs, governance, practice or liturgical norms, even where ostensibly at odds with any of the law’s prohibited categories of discrimination ….

Moreover, the division has not and has no intention to engage in any determination or judgment as to what is or is not a “religious activity” of a church, or to determine what is or is not a “tenet” of religious faith. Within First Amendment limits, all of plaintiffs’ claimed religiously-based free exercises of faith are unthreatened by a reasoned construction of the LAD consistent with its meaning and long enforcement history.

- Based largely on the text of the Stewart affidavit, the appeals court affirmed the district court’s dismissal of the church plaintiffs’ complaint. The court concluded that the case was not “ripe” for resolution since there was no “credible threat of enforcement” against the church defendants.

- However, the court added that the Stewart affidavit did not “disavow enforcement” of the nondiscrimination provisions of the public accommodations laws against the pastor or church members individually, and so the pastor’s claims could be heard. It sent the case back to the district court for further proceedings.

- (6) Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, 734 A.2d 1196 (N.J. 1999) rev’d on other grounds 530 U.S. 640 (2000)

- The New Jersey Supreme Court addressed the efinition of public accommodation:

Our case law identifies various factors that are helpful in determining whether Boy Scouts is a “public accommodation.” We ask, generally, whether the entity before us engages in broad public solicitation, whether it maintains close relationships with the government or other public accommodations, or whether it is similar to enumerated or other previously recognized public accommodations.

Broad public solicitation has consistently been a principal characteristic of public accommodations. Our courts have repeatedly held that when an entity invites the public to join, attend, or participate in some way, that entity is a public accommodation … . An establishment which by advertising or otherwise extends an invitation to the public generally is a place of public accommodation.

[The nondiscrimination provisions in the state public accommodations law] requires “an establishment which caters to the public, and by advertising or other forms of invitation induces patronage generally, [not to] refuse to deal with members of the public who have accepted the invitation.”

- Two conclusions to the question of whether the church is a “place of public accommodation” under applicable local, state, or federal laws.

- While the definition of a “place of public accommodation” varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction under laws prohibiting various forms of discrimination by places of public accommodation, the following generalizations may be helpful.

- First, it is likely that a church that does not invite or solicit the general public to come onto its premises, whether to raise revenue or not, for events or activities unrelated to the core mission of the church, will not be deemed a place of public accommodation and therefore will not be subject to the nondiscrimination provisions in a state or local public accommodations law. This is a generalization that likely will be true in many, perhaps most, cases, but not all. As noted previously, the State of Massachusetts enacted a law in 2016 adding gender identity to the forbidden forms of discrimination by places of public accommodation. The Massachusetts law states:

An owner, lessee, proprietor, manager, superintendent, agent or employee of any place of public accommodation, resort or amusement that lawfully segregates or separates access to such place of public accommodation, or a portion of such place of public accommodation, based on a person’s sex shall grant all persons admission to, and the full enjoyment of, such place of public accommodation or portion thereof consistent with the person’s gender identity.

- The law directed the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination (MCAD) and state attorney general to issue regulations or guidance facilitating the implementation of the new law. The MCAD issued “Gender Identity Guidance,” which states that “a church could be seen as a place of public accommodation if it holds a secular event, such as a spaghetti supper, that is open to the public.” The attorney general also issued its “Gender Identity Guidance for Public Accommodation” and stated on its website that “houses of worship” are places of public accommodation. The attorney general later clarified its position as a result of a lawsuit brought by four churches, and concluded that “while religious facilities may qualify as places of public accommodation if they host a public, secular function, an unqualified reference to ‘houses of worship'” as an example of a place of public accommodation was inappropriate.

- Second, it is likely that a church that invites the general public onto its premises for purposes unrelated to worship or other activities in furtherance of the church’s religious purposes will be deemed a place of public accommodation, especially if the primary purpose in doing so is raising revenue.

Key point. The court in the Iowa case addressed in this article cautioned that its conclusion that the church was not a place of public accommodation might have been different had the church “allowed the use of its facility as commercially available space with no religious limitations placed on such use.” Fort Des Moines Church of Christ v. Jackson, 2016 WL 6089842 (S.D. Iowa 2016).

- These two conclusions cover some cases but not all. For example, what about churches that invite the public onto their premises without charging rent? Does a public invitation transform a church into a place of public accommodation, even if no rent or fees are charged? The answer to this question is unclear. There is no doubt that some courts would deem the public invitation to be sufficient to make the church a place of public accommodation, even if no rent or other fees are charged. But this likely would not be the conclusion of all courts. This makes it essential for church leaders to remain informed about the text and interpretation of the public accommodation laws in their state and city.

- 2. What forms of discrimination are prohibited by places of public accommodation (i.e., is gender identity included)?

- The forms of discrimination forbidden by public accommodations laws vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. And, they are often amended, so it is important for church leaders to be familiar with the current text of applicable public accommodation laws.

- 3. If a state or local public accommodations law defines a “place of public accommodation” to include churches, or is so construed by a court or administrative agency, can a church assert a constitutional defense to coverage based on the First Amendment’s free exercise or nonestablishment of religion clauses?

- As noted previously in this article, several courts and administrative agencies have said that there are constitutional limits on the authority of government agencies to enforce the nondiscrimination provisions of public accommodation laws against churches. To illustrate, in the Iowa district court ruling addressed in this article, the court ruled that a church’s fear of being sued for violating a public accommodations law as a result of sermons on biblical sexual morality was too fanciful to give the church “standing” to pursue its claim in federal court. The court concluded:

Plaintiff alleges that it fears prosecution under the state and municipal discrimination bans if … its pastor delivers his sermon about biological sex and the Bible. However [this fear] is not objectively reasonable. All of the statutes, the ordinances, and the interpretations of the provisions appearing in the [state civil rights agency’s] guidance documents include an exemption for religious institutions when conducting religious activities. Although the definitive scope of this exemption is yet to be determined, the court concludes the delivery of a sermon by a pastor of a church is undoubtedly an act intended to serve “a bona fide religious purpose.” Indeed, it is a quintessential religious activity. See Fowler v. State of R.I., 345 U.S. 67 (1953) … [in which the Supreme Court ruled] that it is not within “the competence of courts under our constitutional scheme to approve, disapprove, classify, regulate, or in any manner control sermons delivered at religious meetings,” and “sermons are as much a part of a religious service as prayers.” Hence, plaintiff’s allegedly chilled course of conduct is not even arguably proscribed by the statute. Rather, it is expressly permitted. Accordingly, plaintiff’s fear of enforcement consequences if it delivers the sermon is not objectively reasonable because it does not face a credible threat of prosecution on that basis … . A plaintiff cannot show a threat of prosecution under a statute if it clearly fails to cover his conduct.

- Similarly, in Presbytery of New Jersey v. Florio, 40 F.3d 1454 (3rd Cir. 1994) aff’d 99 F.3d 101 (1996), a federal district court in New Jersey ruled that the New Jersey Law Against Discrimination (NJLAD), which prohibits discrimination on various grounds including gender identity and sexual orientation in any “place of public accommodation,” did not apply to a church. The court relied on an affidavit submitted by the director of the state division of civil rights (the Stewart affidavit) setting forth the position of the division and state attorney general regarding enforcement of the nondiscrimination provisions in the state public accommodations law against religious institutions. The Stewart affidavit affirmed that the state did not consider churches places of “public accommodations,” and so the sections relating to public accommodations were “inapplicable to the church plaintiffs.” The Stewart affidavit also made the following general statement:

It has been the consistent construction and interpretation of the [law] that, consonant with constitutional legal barriers respecting legitimate belief and free exercise protected by the First Amendment, the state was not authorized to regulate or control religious worship, beliefs, governance, practice or liturgical norms, even where ostensibly at odds with any of the law’s prohibited categories of discrimination ….

Moreover, the division has not and has no intention to engage in any determination or judgment as to what is or is not a “religious activity” of a church, or to determine what is or is not a “tenet” of religious faith. Within First Amendment limits, all of plaintiffs’ claimed religiously-based free exercises of faith are unthreatened by a reasoned construction of the NJLAD consistent with its meaning and long enforcement history.

- Conclusion

- At this time, the most viable basis of liability for churches that assign restrooms based solely on gender at birth is a state or local law forbidding discrimination by “places of public accommodation” on the basis of gender identity. A growing number of states and cities have enacted such a law. With that in mind, churches would be wise to work through the following seven questions:

- Is there a public accommodations law in my city or state?

- If so, does it prohibit discrimination based on gender identity?

- Does the law provide an exemption for churches?

- If the law provides an exemption for churches, are there any conditions that must be satisfied?

- If the law does not contain an explicit exemption for churches, what is the official position of the civil rights agency tasked with enforcement of the law? Does the agency take the position that churches are exempt? And if so, do any conditions apply? For example, does the exemption apply to churches that rent their property to raise revenue?

- If a state or local civil rights agency tasked with enforcement of a public accommodations law claims that it applies to churches that are engaged in commercial or other activities unrelated to exempt, religious purposes, does church coverage only apply during the use of church property for the unrelated purpose, or more broadly to include all uses of church property?

- Does a church have a constitutional right under the First Amendment guarantee of religious freedom to restrict restroom usage based on gender at birth? If so, do conditions or exceptions exist? What have the courts said about this, especially courts in the jurisdiction where the church is located?

- Note: This article does not address other issues associated with discrimination based on gender identity, including discrimination in employment and discrimination by secular businesses (i.e., bakers, photographers) based on the religious beliefs of the owners.

- The Application of Public Accommodation Laws to Churches:a review of the leading cases in chronological order

-

case

holding

Traggis v. St. Barbara’s Greek Orthodox Church, 851 F.2d 584 (2d Cir. 1988)

A church had not violated a Connecticut law banning several kinds of discrimination for places of public accommodation because churches are not a place of public accommodation.

Roman Catholic Archdiocese v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 548 A.2d 328 (Penn. 1988)

Parochial schools run by a Catholic church are not places of public accommodation under Pennsylvania law.

Presbytery of New Jersey v. Florio, 40 F.3d 1454 (3rd Cir. 1994) aff’d 99 F.3d 101 (1996)

In dismissing a church’s request for an injunction barring the state from applying against churches a public accommodations law banning discrimination based on sexual orientation, the court relied, in part, on the following assurance provided by a state civil rights agency: “It has been the consistent construction and interpretation of the [law] that, consonant with constitutional legal barriers respecting legitimate belief and free exercise protected by the First Amendment, the state was not authorized to regulate or control religious worship, beliefs, governance, practice or liturgical norms, even where ostensibly at odds with any of the law’s prohibited categories of discrimination.”

Wazeerud-Din v. Goodwill Home & Missions, Inc., 737 A.2d 683 (1999)

A church’s addiction program was not a place of public accommodation under New Jersey law; the group was essentially religious in nature in that it devoted time to the study of Christian tenets and “a religious institution’s solicitation of participation in its religious activities is generally limited to persons who are adherents of the faith or at least receptive to its beliefs.”

Donaldson v. Farrakhan, 762 N.E.2d 835 (Mass. 2002)

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court considered whether a public accommodation law applied to a religiously affiliated event that was not open to women. The event in question was a speaking event promoted, organized, and funded by a mosque, and presented by minister Louis Farrakhan at a city-owned theater, to address drugs, crime, and violence in the community. The court found that the event was not a “public, secular function” of the mosque. The court also found that application of the public accommodation law to require the admission of women to the event “would be in direct contravention of the religious practice of the mosque” because it would impair the “expression of religious viewpoints” of the mosque with respect to the “separation of the sexes” and the role of men in the community. The court thus further held that the “forced inclusion of women in the mosque’s religious men’s meeting by application of the public accommodation statute” would “significantly burden” the mosque’s First Amendment rights of expression and association.

Sailant v. City of Greenwood, 2003 WL 24032987 (S.D. Ind. 2003)

“The church is not a place of public accommodation.”

Vargas-Santana v. Boy Scouts of America, 2007 WL 995002 (D.P.R. 2007)

“As a matter of law, a church is not a place of public accommodation.”

Abington Friends School, 2007 WL 1489498 (E.D. Pa. 2007)

In a case involving the interpretation of the exemption of religious organizations from the public accommodations discrimination provisions in the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the court quoted from the ADA regulations: “Although a religious organization or a religious entity that is controlled by a religious organization has no obligations under the rule, a public accommodation that is not itself a religious organization, but that operates a place of public accommodation in leased space on the property of a religious entity, which is not a place of worship, is subject to the rule’s requirements if it is not under control of a religious organization. When a church rents meeting space, which is not a place of worship, to a local community group or to a private, independent day care center, the ADA applies to the activities of the local community group and day care center if a lease exists and consideration is paid.” 28 C.F.R. Pt. 36, App. B (2007).

Sloan v. Community Christian School, 2015 WL 10437824 (M.D. Tenn. 2015)

This case addressed the definition of “a place of public accommodation” under Title III of the ADA rather than a state or local public accommodations law. Nevertheless, its discussion of this key term provides some clarification, even if by inference. It suggests that churches that operate “a day care center, a nursing home, a private school, or a diocesan school system,” may be places of public accommodation subject to the nondiscrimination provisions of a local or state public accommodations law.

Barker v. Our Lady of Mount Carmel School, 2016 WL 4571388 (D.N.J. 2016)

“Although churches, seminaries and religious programs are not expressly excluded from the definition of ‘place of public accommodation,’ the legislature clearly did not intend to subject such facilities and activities to the [public accommodations law]. Thus, the claims against these institutional defendants fail as a matter of law.”

Fort Des Moines Church of Christ v. Jackson, 2016 WL 6089842 (S.D. Iowa 2016)

A court refused to issue an injunction preventing state and local public accommodation laws from being enforced against Fort Des Moines Church of Christ, since there was no injury to be redressed. The court referenced an exception in the law for churches, and an affidavit from the state and city defendants that they had never applied the law to churches. But the court cautioned that a church that “engages in non-religious activities which are open to the public” would not be exempt, and it cited as examples “an independent day care or polling place located on the premises of the place of worship.”