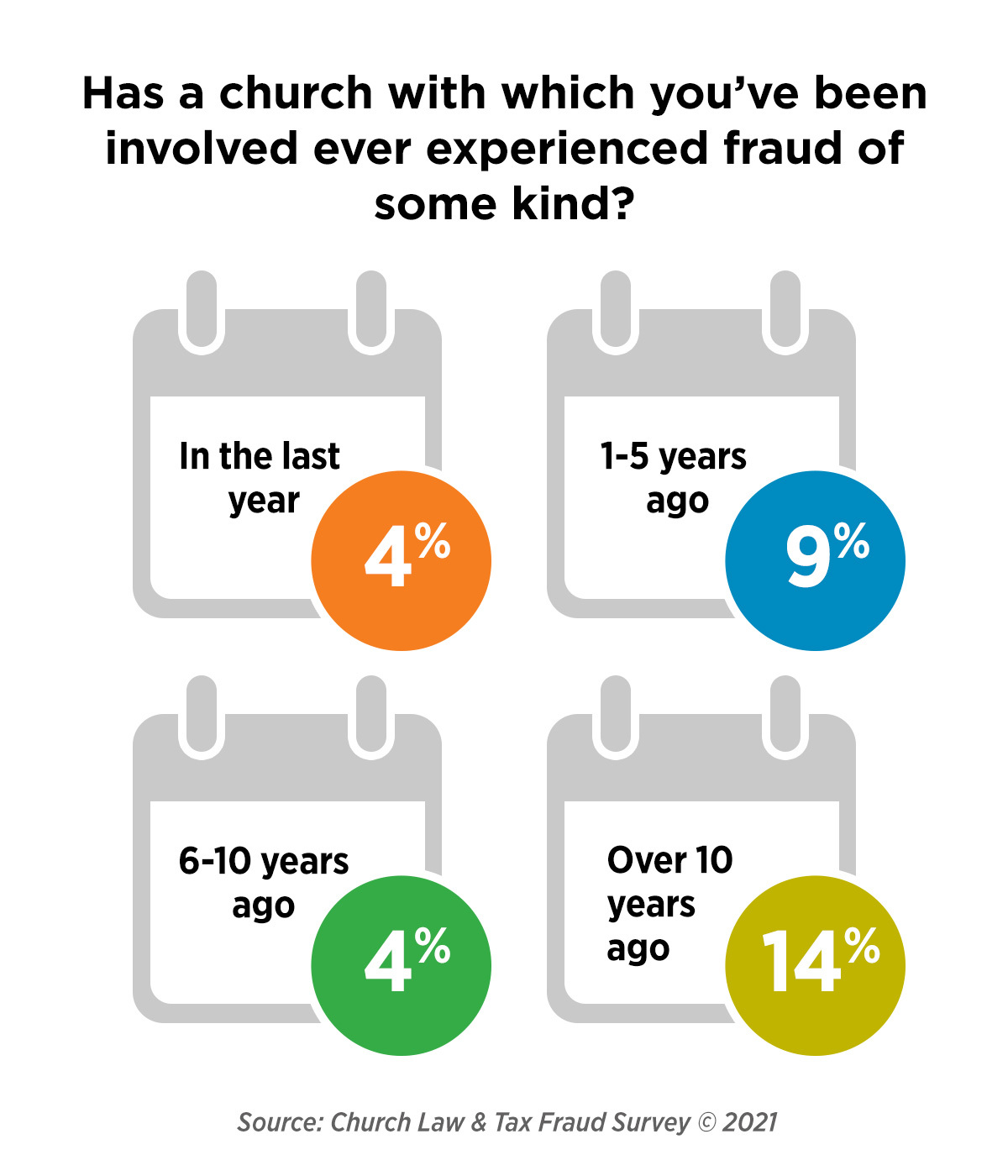

A nationwide survey of more than 700 church leaders conducted by Church Law & Tax shows nearly one-third serve in congregations that have suffered from some form of financial misconduct.

Among those experiencing it, half said an incident occurred within the past 10 years.

Prior research conducted by other organizations throughout the past 20 years has usually pegged the figure closer to 10 percent or 15 percent for houses of worship. Still, church financial experts have long estimated that the figure was at least one-third or even higher for all congregations across the nation—a figure that appears to track closely with the Church Law & Tax study from 2021.

“It was disheartening to see 30 percent of churches responding had experienced fraud,” said CPA Vonna Laue, a senior editorial advisor for Church Law & Tax who co-led the survey project. “It did confirm to me how prevalent this situation is in churches.”

Churches of all sizes, ages, and locations are susceptible, according to the survey’s findings—and fraud prevention experts say the vulnerabilities that perpetrators commonly exploit are ones easily remedied.

“The primary types of financial misconduct that occurred are the most preventable with a good internal control structure,” Laue said.

Yet many churches do not install simple safeguards out of a perceived high level of trust among their ranks, a noted frustration among the financial experts who reviewed Church Law & Tax’s results and provided comment.

“It will never happen here”

Two-thirds of survey respondents who said they weren’t aware of fraud in their churches also said they believe the problem is unlikely or “will never” happen in their churches. Ironically, among those who endured misconduct, half said they shared a similar “it-will-never-happen” sentiment before uncovering a case—and 80 percent then implemented several basic measures after the fact.

“This is one of the most important takeaways from this study,” noted Rollie Dimos, a Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE) and author of Integrity at Stake: Safeguarding Your Church from Financial Fraud. “Most people think that their church is immune from the risk of fraud because [their] staff and volunteers are trustworthy. . . . We trust people to do the right thing, but we can fail them if we don’t hold them accountable or provide controls to protect them.”

Nathan Salsbery, a CFE and a partner and executive vice president for nonprofit CPA firm CapinCrouse, said many congregations “do not implement effective internal controls until they feel the pain of fraud firsthand.”

Salsbery is currently assisting fraud investigations at three different churches. “Had these churches implemented a few basic internal controls, they would have either prevented the fraud or would have detected it much sooner,” he added.

A costly toll

The failure to prevent or quickly detect financial misconduct exacts heavy tolls on congregations. In a 2022 study, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary’s Center for the Study of Global Christianity estimates church fraud globally will total $70 billion a year by 2025.

The fallout extends beyond pure dollars, though, and often with devastating effects. In an analysis of the language used by respondents to Church Law & Tax’s survey, words associated with anger and sadness appeared repeatedly among respondents who experienced fraud.

“The financial losses can be staggering,” Salsbery said. “While the financial losses are bad enough, there are usually many other losses that result from the inevitable broken trust and relationships damaged by such long-term acts.”

Such damage is understandable, given the typical identity of the perpetrator and the amounts that he or she steals.

As the Church Law & Tax research shows, the profiles of offenders frequently included treasurers, board members, and middle-aged pastors. Financial losses were the largest among perpetrators with long tenures at their churches (see “Loved and Trusted: What Shocks Us Most about Fraud Perpetrators”).

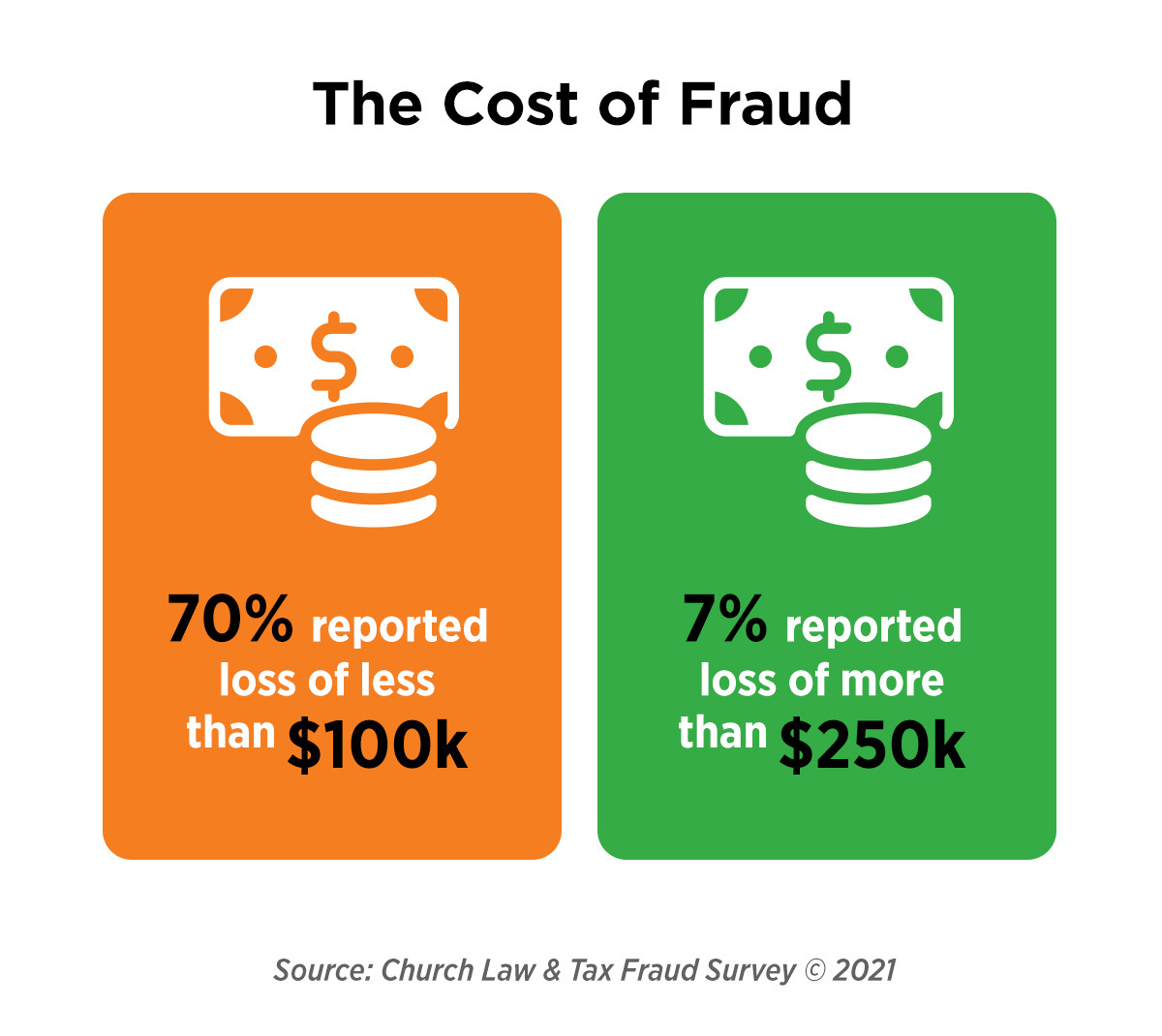

As for the amounts stolen, Church Law & Tax’s research showed 69 percent of those victimized said their losses measured less than $100,000. About 14 percent said the amounts topped $100,000, while another 15 percent said they did not know how much was taken.

Precise financial losses are difficult to pinpoint since the perpetrator may not know or may lie. And churches that choose not to contact law enforcement likely will miss out on learning the full extent because a thorough investigation never happens. Nearly 70 percent of victimized churches chose not to report their cases to police. Overall, only 22 percent of all respondents said their boards would contact law enforcement in the event a future suspected or actual case arose (see “Reporting Financial Crime as a Matter of Stewardship”).

Easy opportunities

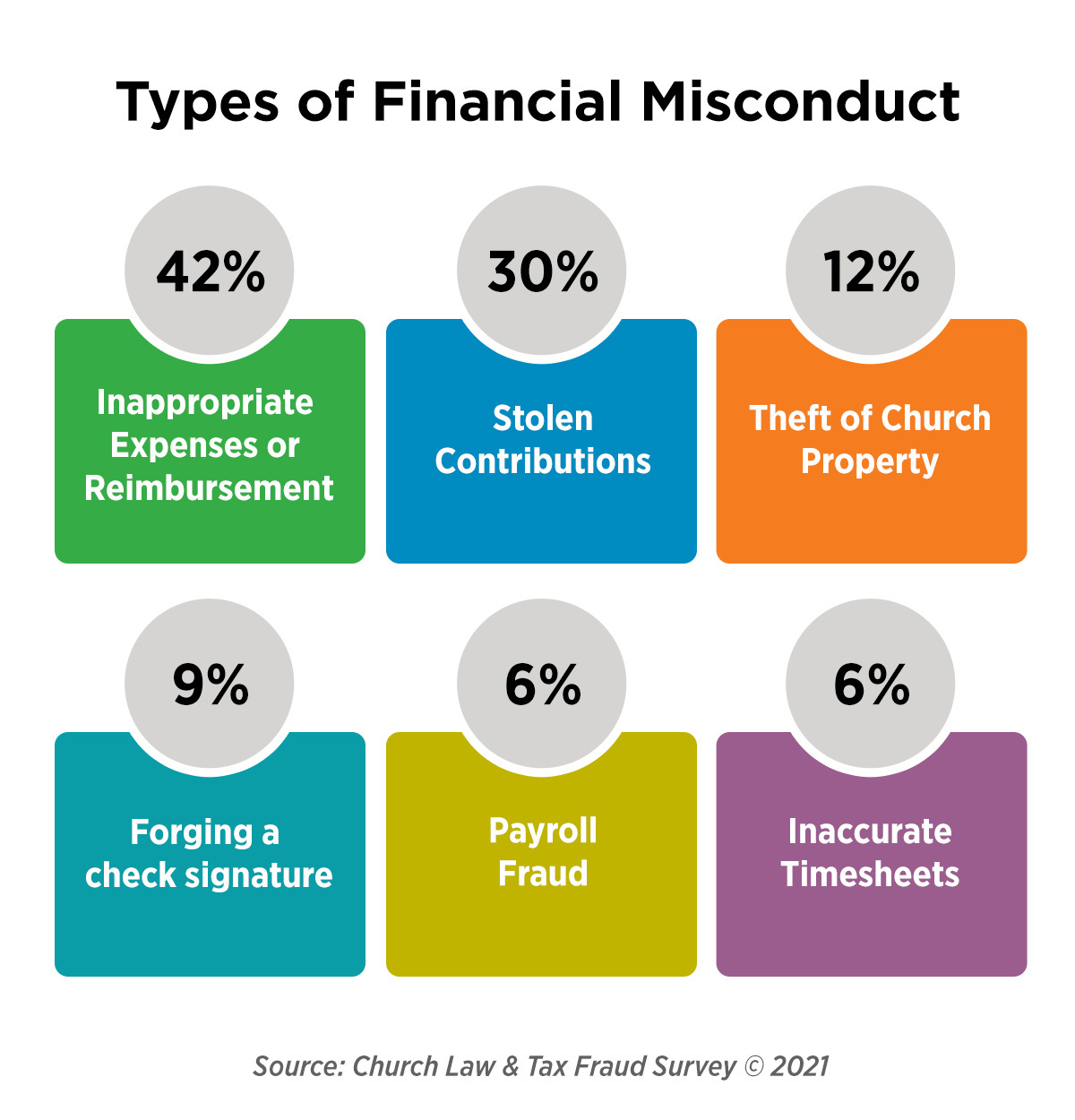

Nearly 42 percent of cases involved “inappropriate expenses or inappropriate expense reimbursements,” the survey showed. Slightly more than 30 percent involved stealing contributions. Payroll fraud and inaccurate timesheets combined constituted 12 percent of the cases. And another 11 percent took tangible church property, while about 9 percent forged check signatures. (Note: Respondents to the “Types of Financial Misconduct” infographic were asked to check all that apply.)

While the type of theft men and women committed against their churches varied, according to the survey, it generally boiled down to one thing: easy opportunities.

“While TV shows often depict fraud as grand and complicated schemes, most fraud committed in the church is simply an individual taking advantage of a situation where no one is looking,” Salsbery observed.

Just assigning another set of eyes to monitor a variety of financial activities could greatly reduce easy opportunities. For instance, the leading “red flag” for persons who committed fraud was excessive control over his or her duties or an “unwillingness to have others cover his/her job duties.”

“Nearly half of fraud schemes found were detected as a result of another employee performing a person’s duties” in their absence, noted CPA Michael Batts, another Church Law & Tax senior editorial advisor who reviewed the results. “The rotating duties of workers performing certain financial duties is, itself, an effective internal control mechanism, especially where adequate segregation of duties for a particular position is not in place.”

Encouraging signs—but much room for improvement

While the ease with which perpetrators stole from their churches is troubling, many of the practices best positioned to thwart such efforts do not require extensive time or expense.

On an encouraging note, many respondents indicated at least some best practices are already in place.

About 86 percent of all respondents regularly generate and review financial statements, and 83 percent make certain two unrelated people work together to handle financial tasks.

Around three-quarters of those who had experienced fraud said they use separate individuals—the “segregation of duties” in accounting parlance—for authorizing cash disbursements, maintaining custody or control over cash, and handling accounting responsibilities. (Note: Most of those who responded to the question about “segregation of duties” were in churches that had experienced fraud. Respondents highlighted in the “Top measures churches take to prevent financial misconduct” infographic were asked to check all that apply.)

Still, the responses for these categories show between 17 percent and 25 percent of churches are not performing these basic measures.

The percentages worsen when considering other areas of financial accountability or internal controls recommended by experts. For instance:

- Slightly more than half of respondents said one person in their church has the ability to perform all aspects of cash disbursements without requiring another individual’s involvement. “That is a staggering statistic,” Laue noted.

Dimos said this problem, along with improper expenses or expense reimbursements—the leading type of fraud found in the survey—can be easily prevented by “[r]equiring a second person to review and approve all credit card purchases or reviewing invoices or reimbursement requests before signing checks.”

Additionally, “disciplined monthly reviews of cancelled checks (or images) and reviews of monthly credit card statements and related documentation and support [can] significantly reduce risk,” Salsbery said.

- Only one-third of churches store their collections in a safe and secure manner and require dual controls for access when they cannot be immediately deposited at the bank (again, stolen contributions constituted the second-highest type of fraud in the survey).

- Only one-third of churches have their payroll approved by someone other than the preparer and then reconciled to the church’s accounting system.

- Only 22 percent apply accounting procedures to tangible property susceptible to theft, such as electronic equipment or bookstore inventories.

“The addition of internal controls to protect your church will not cost the church anything,” Dimos observed. “Having a second person—like a staff member, trusted volunteer, or board member—be responsible to review the bank reconciliation and bank statements, or review a general ledger detail report, can provide a great deal of accountability, but not add any extra expense for the church.”

Audits and assessments

Financial audits and fraud risk assessments offer additional protections for churches, although unlike the previously mentioned preventive steps, these typically come with a cost.

An ongoing audit process “can help a church greatly reduce the risk of misappropriation and embezzlement,” Batts said. Dimos agreed, adding the use of fraud risk assessments can go one step further and “help a church test their controls and identify potential weaknesses and risk areas.”

In the survey, about 24 percent of respondents conducted outside audits with a CPA, which involves documentation and third-party support of the financial information, Laue said. Thirty percent hired a CPA or financial expert to perform a less intensive outside review, which relies on inquiries and analytical procedures, Laue noted. Almost 38 percent said they perform internal audits using church staff and volunteers.

In terms of fraud risk assessments, nearly 51 percent said they do not use them at all.

Learning from “hard lessons”

Church Law & Tax’s survey “presents a strong case for churches to be proactive in preventing fraud,” Dimos said.

The fact that 30 percent of churches reported experiencing financial misconduct at some point, and that the possibility exists even more experience it without realizing it, reveals “the risk of fraud is very real in all churches,” Salsbery said.

While many will think the steps are unnecessary, or shouldn’t be necessary because people should know better, Salsbery pointed to examples of fraud contained in the Bible—including Judas’s thefts from Jesus and the disciples’ ministry account or Ananias and Sapphira’s attempt to deceive Peter—as reminders that anyone can succumb to temptation.

“Just as policies are put in place to help prevent other sins from damaging the church, controls are needed to protect churches from the sin of fraud,” Salsbery said.

And taking time now to review practices and strengthen them—especially when no apparent problem exists—only ensures church leaders are stewarding resources well, Laue added.

“Let’s learn from the hard lessons of others,” Laue said. “I strongly encourage churches to take the step and carefully review internal controls or even hire someone to help assess and implement better internal controls now. Even if fraud was never to occur, it won’t hurt for us to operate with good processes in place.”

NEW! Safeguarding Your Church’s Finances—a multi-session video course for pastors, board members, staff, and volunteers on the basics of fraud prevention. LEARN MORE!