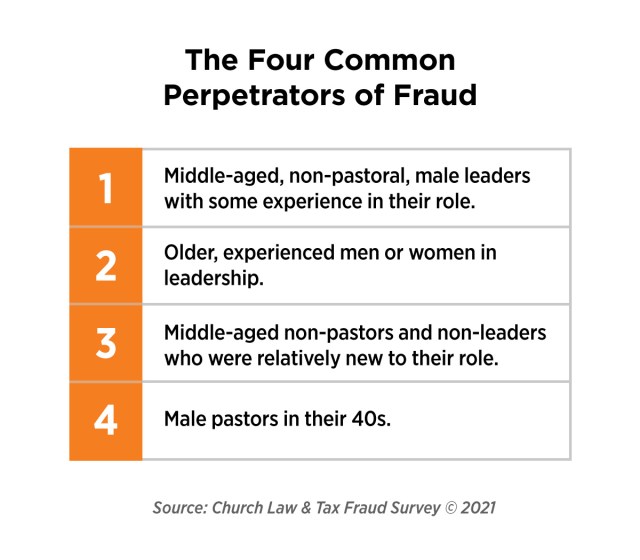

Church Law & Tax’s nationwide survey of congregations and the financial misconduct they experience paints four portraits of the types of individuals who most commonly steal from their churches.

What’s most shocking?

The positions of trust the men and women who commit these crimes carry.

The study revealed that common perpetrators included middle-aged men who served as treasurers or board members, sometimes for upwards of 10 years; men and women in their 30s and 40s who worked in their roles as administrators and treasurers for less than 5 years; and male pastors in their 40s.

And then there’s the group of perpetrators that may be the most surprising of all: men and women, typically 60 or older, who held their positions for 20 years or more. The crimes committed by these individuals “were disproportionately expensive” compared with other offenders, according to Arbor Research Group, the firm Church Law & Tax commissioned to survey church leaders nationwide.

“Just as fraud can happen in any sized church, fraudsters can be any age, any gender, and perform any function in the church,” said Rollie Dimos, a Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE) who reviewed the survey results ahead of publication and provided comment. “That’s why it is so important to put financial processes in place to actually protect our church team members from being tempted to steal God’s money. Internal controls are like guardrails that help keep people honest and accountable.”

Portraits of the perpetrators

The national survey fielded responses from 706 leaders and revealed nearly 30 percent served in churches that had experienced some form of financial misconduct. Nearly half said the crimes occurred within the past 10 years (see “Every Church Is at Risk for Fraud. Here’s Why”).

Those who suffered from some form of fraud answered questions exploring the acts committed and the people responsible for them. Through those responses, Arbor was able to classify the four classes of perpetrators, shedding more light on the common traits they possess.

Class 1

Arbor characterized this group as “middle-aged, non-pastoral male leaders with some experience in their roles.” These men frequently served as treasurers, board members, or in non-pastoral leadership roles.

Class 2

This group constituted “older, experienced men or women in leadership,” Arbor noted. They often served in their roles—which varied—for 20 years or more. A quarter of these cases resulted in losses of $250,000 or more, while half caused losses ranging anywhere from $10,000 to $250,000.

“The worst-case scenario for a church is to have fraud committed by long-tenured leaders in the church,” said Nathan Salsbery, a CFE and a partner and executive vice president for nonprofit CPA firm CapinCrouse who also previewed the survey results. “And if those leaders had unmonitored access to the cash coming in, the cash going out, and the accounting records, the financial losses can be staggering.”

Class 3

This class featured the highest number of perpetrators, Arbor said. It, too, was evenly represented by men and women, but their ages ranged from 30 to 49 and their average tenures were 5 years or less. Among these individuals, about one-third worked as administrators, while 20 percent served as treasurers. Overall, 20 percent were unpaid volunteers.

Class 4

This group was comprised entirely of male pastors “typically 40 to 49 years of age and in their role 1 to 5 years,” Arbor noted. The thought of a pastor betraying his congregation in this way exacts significant tangible and intangible damage, Salsbery noted. “Lack of healthy accountability for senior leadership is one of the most significant risks to a church,” he said.

Red flags to monitor

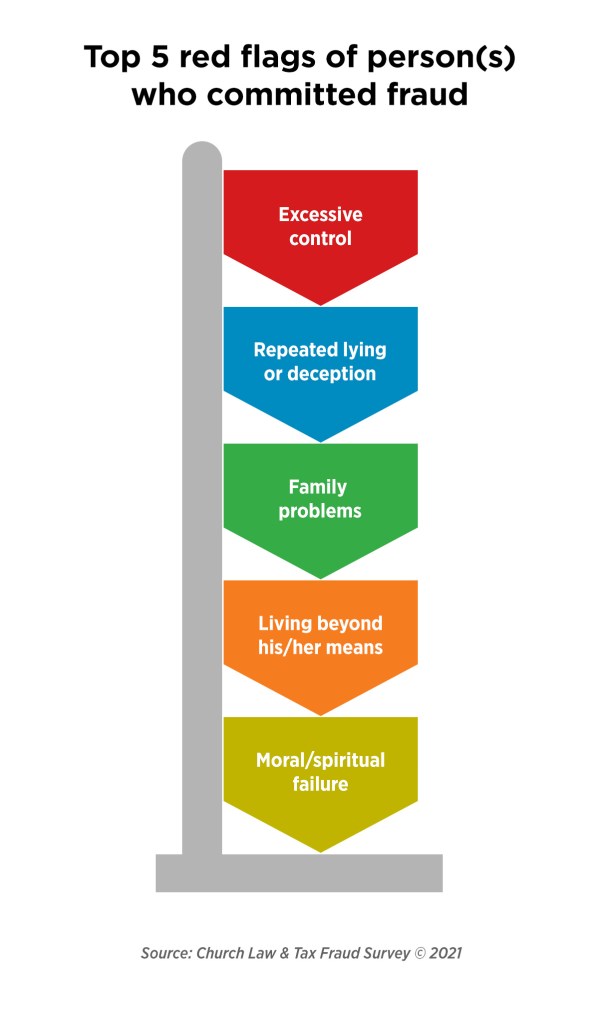

The top “red flag” identified among the fraud cases disclosed in the survey—representing 32 percent—was “excessive control or unwillingness to have others cover his/her job duties,” according to the results. In fact, 47 percent of the cases weren’t discovered until another person performed the perpetrator’s duties for one reason or another.

The second-highest red flag was “repeated lying or deception,” followed by “family problems,” “living beyond his/her means,” and “other moral or spiritual failures.”

Lower on the list were “medical issues in family,” “expressed lack of job satisfaction,” and “loss of spouse’s job.”

When asked about red flags, a sizable portion of respondents selected “Other.” Asked to clarify, the bulk of the respondents said there either were no red flags, the person wasn’t caught and the fraud was later detected, or the red flags weren’t exhibited within the church and only learned of later.

In his comments about red flags, Dimos noted the “fraud triangle”—the illustration often used to describe financial misconduct. It forms a triangle with these three points: pressure (or incentive), rationalization, and opportunity.

“As church leaders, we can’t control what financial pressure someone may experience, like a family medical issue, nor can we stop people from rationalizing that it is okay to steal from the church,” he said. “But church leaders can create processes that prevent someone from having the opportunity to abuse funds.”

Red flags are consistent in other sectors

Interestingly, Church Law & Tax’s survey results closely tracked with the 2020 Report to the Nations by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE), Salsbery said. In particular, with greater positions of authority and tenure came greater degrees of losses for the organizations, he added.

The ACFE report showed the median losses for employee-caused fraud measured $21,000, then jumped to $95,000 for managers and supervisors, and $250,000 for executive-level positions.

“This correlation of higher fraud losses for long-tenured, experienced leaders makes sense. Given their influential leadership roles, they usually have more access to the assets of the church and have had that access for a long time,” Salsbery said. “The first two questions I ask ministries when I conduct [fraud investigations] is: (1) How long was the person in the role? and (2) What access did they have to bank accounts, other assets, and financial activities of the church during that time?”

Given the frequency and consistency of the red flags, whether in secular settings or church settings, leaders are actually positioned well to help protect their churches, noted Vonna Laue, a CPA and senior editorial advisor for Church Law & Tax who co-led the survey project.

“The red flags have not changed over the years in any study you review, and they are the same across entities from churches to Fortune 500 companies,” Laue said.

Leaders need “an awareness of the red flags,” she added, and give careful consideration when those serving in financial roles exhibit “at-risk behaviors.”

NEW! Safeguarding Your Church’s Finances—a multi-session video course for pastors, board members, staff, and volunteers on the basics of fraud prevention. LEARN MORE!