Key point 8-10.01. The civil courts have consistently ruled that the First Amendment prevents the civil courts from applying employment laws to the relationship between a church and a minister.

An Indiana federal court ruled that the ministerial exception barred it from resolving the discrimination claims of a school counselor who was fired from a Catholic school for entering into a same-sex marriage.

The plaintiff’s termination

A woman (the “plaintiff”) worked for a private Catholic school (the “school”) in Indianapolis, Indiana, for nearly 40 years. After the school learned of her same-sex marriage, it declined to renew her employment contract on the grounds that her marriage violated Catholic teachings.

At the time of her termination, the plaintiff worked as Co-Director of Guidance Counseling. The plaintiff sued the school and the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Indianapolis. She alleged discrimination, retaliation, and hostile work environment under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and interference with an employment relationship under state law.

The school filed a “motion for judgment on the pleadings,” asking the trial court to dismiss all of the plaintiff’s claims on the ground that she was a minister for purposes of the “ministerial exception.” The ministerial exception—a legal doctrine recognized by the US Supreme Court that is based upon the First Amendment’s religion clauses—generally bars the civil courts from resolving employment disputes between churches and ministers.

The trial court denied the school’s request. The school appealed, but a federal court affirmed the lower court’s ruling, allowing the case to proceed.

The school subsequently sought a “motion for summary judgment” in its favor, again arguing the ministerial exception applied. This time the federal court granted the motion. The decision provides churches and church-run schools with further insights into how courts continue to interpret and apply the doctrine.

Background: Understanding the plaintiff’s employment and her roles

The school operates “under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Indianapolis.” According to the school’s mission statement, it pledges to “provide . . . an educational opportunity which seeks to form Christian leaders in body, mind, and spirit.” The school’s purpose is to “support and otherwise further the mission and purposes of” the archdiocese.

The court recounted the progression of the plaintiff’s employment and the school’s communications throughout her tenure.

The plaintiff’s employment

The plaintiff began working at the school during the 1978–1979 school year, and with the exception of the 1981–1982 school year (when she completed a master’s degree in music education), she worked there continuously until her termination in 2019.

She held several positions during her time at the school, including New Testament teacher, Choral Director, Fine Arts Chair, Guidance Counselor, and Co-Director of Guidance. She taught New Testament from 1982 to 1989.

In 1985, the school’s chaplain told the plaintiff that she must apply for catechesis certification in order to continue teaching religion, so she applied to become a catechist. Her application was approved, but it expired in 1990 and she never renewed it.

From 1988 to 1998, the plaintiff served as Choral Director, a role which required her to prepare students for the music used during the school’s monthly Mass.

In 1997, the plaintiff became a guidance counselor, a position she held for 10 years until she assumed the role of Co-Director of Guidance in 2007. She served as Co-Director of Guidance for 12 years until her termination in 2019.

Role as guidance counselor

Teachers and guidance counselors at the school are generally employed pursuant to one-year contracts. When this dispute arose, the plaintiff was employed under a “School Guidance Counselor Ministry Contract” and accompanying “Archdiocese of Indianapolis Ministry Description.”

According to the contract, the plaintiff agreed that she would be in default if she breached any duty, which included “relationships that are contrary to a valid marriage as seen through the eyes of the Catholic Church.” The Catholic Church defines marriage as a covenant “by which a man and a woman form with each other an intimate communion of life and love” (Catechism of the Catholic Church § 1660).

The contract also provided that the plaintiff “acknowledge[d] receipt of the ministry description that is attached to this contract and agree[d] to fulfill the duties and responsibilities listed in the ministry description.”

The ministry description identifies a guidance counselor as a “minister of the faith” who will “collaborate with parents and fellow professional educators to foster the spiritual, academic, social, and emotional growth of the children entrusted in his/her care.” The ministry description further specified:

As role models for students, the personal conduct of every school guidance counselor, teacher, administrator, and staff member, both at school and away from school, must convey and be supportive of the teachings of the Catholic Church.

The first “Role” identified in the ministry description is that the guidance counselor “Facilitates Faith Formation,” which included the following responsibilities:

- “Communicates the Catholic faith to students and families through implementation of the school’s guidance curriculum, academic course planning, college and career planning, administration of the school’s academic programs, and by offering direct support to individual students and families in efforts to foster the integration of faith, culture, and life.”

- “Prays with and for students, families, and colleagues and their intentions. Participates in and celebrates liturgies and prayer services as appropriate.”

- “Teaches and celebrates Catholic traditions and all observances in the Liturgical Year.”

- “Models the example of Jesus, the Master Teacher, in what He taught, how He lived, and how He treated others.”

- “Conveys the Church’s message and carries out its mission by modeling a Christ-centered life.”

- “Participates in religious instruction and Catholic formation, including Christian services, offered at the school.”

Guidance counselors were also expected to “use techniques and methods that foster a Christ-centered atmosphere”; “participate in spiritual retreats, days of reflection, and spiritual formation programs”; “proactively identif[y] and address physical, social, emotional, and spiritual needs of individuals and of the community of learners”; and “display Gospel values.”

The guidance department is also the only department whose staff members meet with every student individually throughout the year.

Role as Co-Director of Guidance

In her role as a guidance counselor and Co-Director of Guidance, the plaintiff attended monthly Masses, where she received communion, sang with the congregation, and also communicated guidance to other staff members regarding how to prepare students of different faiths for the school’s Catholic liturgy.

In addition to attending monthly Masses at the school, the plaintiff attended “Days of Reflection.” The school’s principal explained that these events, which occur before each school year, are “designed specifically for [the school’s] faculty and have a very direct, intentional focus on [the] Catholic mission and how each [faculty member] is called to live out that mission in [their] specific roles.”

The principal further explained that these gatherings are required only for the small group of faculty members “who are impacting kids in their spiritual life on a day-to-day basis.” This included guidance counselors.

At these Days of Reflection, the principal delivers a “call-and-response Commissioning Prayer” which “exhorts” the faculty members to embrace the Catholic ministry at the school. In that prayer, the faculty state that they “accept the responsibilities of [their] ministry”; “promise to share [their] faith with others”; and “promise to form youth and support families in the faith by following the example of our Master Teacher, Jesus Christ.”

At the end of the prayer, the leader states: “I hereby commission you to faithfully and joyfully serve as ministers of the faith in the Catholic schools of the Archdiocese of Indianapolis.”

Prayer is a regular occurrence at the school. Every morning different members of the school community would deliver a morning prayer over the school PA system. The plaintiff delivered the morning prayer on more than one occasion, as did several other individuals, including the principal, the chaplain, the campus minister, and students. While the plaintiff did not otherwise lead prayer or pray with students as part of her regular duties as guidance counselor or Co-Director of Guidance, other guidance counselors testified that prayer with students is a regular part of their job.

Applying the ministerial exception

In granting the school’s motion for summary judgment, the Indiana federal court analyzed the doctrine of the ministerial exception.

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution provides, in part: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” These two “religion clauses” ensure that, among other things, religious institutions are free “to decide matters of ‘faith and doctrine’ without government interference,” said the Indiana court, quoting the Supreme Court’s decision in Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church & School v. E.E.O.C., 565 U.S. 171 (2012).

The federal court noted this quote from a 2020 Supreme Court decision in Our Lady of Guadalupe:

This does not mean that religious institutions enjoy a general immunity from secular laws, but it does protect their autonomy with respect to internal management decisions that are essential to the institution’s central mission. And a component of this autonomy is the selection of the individuals who play certain key roles. Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru, 140 S. Ct. 2049 (2020).

The Indiana federal court said the ministerial exception dictates that “courts are bound to stay out of employment disputes involving those holding certain important positions within churches and other religious institutions,” again quoting the Supreme Court’s decision in Our Lady of Guadalupe.

The court concluded that the plaintiff’s position as Co-Director of Guidance fell within the ministerial exception:

To begin, religious instruction and formation are central to [the school’s] philosophy and mission, and [the plaintiff’s] employment documents “specified in no uncertain terms” that [the school] expected her to perform a variety of religious duties and to help carry out the school’s mission. . . . While [the school’s] characterization of the role is not dispositive, “the school[’s] definition and explanation of the role is important. . . .”

The School Guidance Counselor Ministry Description designated a guidance counselor as a “minister of the faith” and charged her with “foster[ing] the spiritual . . . growth” of her students. The ministry description stated that “Catholic schools are ministries of the Catholic Church, and school guidance counselors are vital ministers sharing the mission of the Church. School guidance counselors are expected to be role models and are expressly charged with leading students toward Christian maturity and with teaching the Word of God.” The ministry description also identified “Facilitates Faith Formation” as the guidance counselor’s first “Role,” which required communicating the Catholic faith to students, praying with and for members of the [school] community, teaching and celebrating Catholic traditions, modeling the example of Jesus, conveying the Church’s message, and participating in religious instruction and Catholic formation. Like the employee in Hosanna-Tabor, [the plaintiff] was “expressly charged”. . . with “leading students toward Christian maturity and with teaching the Word of God.”

The court noted that the plaintiff downplayed the religious nature of her role, and highlighted her secular duties, such as scheduling students for classes, helping students with college applications, providing SAT and ACT test prep tools, administering AP exams, and offering career guidance. She also testified that she did not pray with her students as part of her regular duties as guidance counselor or Co-Director of Guidance, though she did deliver the morning prayer on more than one occasion.

The court then stated:

[T]hat the plaintiff characterizes her work as a guidance counselor in purely secular terms does not change the result because it would be inappropriate for this court to draw a distinction between secular and religious guidance offered by a guidance counselor at a Catholic school. . . . Here, what qualifies as secular or religious guidance in the context of a Catholic high school is exceedingly difficult to identify, and “the purpose of the ministerial exception is to allow religious employers the freedom to hire and fire those with the ability to shape the practice of their faith.”

The court concluded that the ministerial exception barred all of the plaintiff’s claims.

What this means for churches

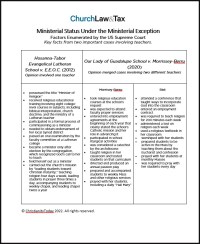

In the 2012 Hosanna-Tabor case, the Supreme Court unanimously affirmed the ministerial exception, but it declined to define the term “minister.” That is understandable, since it would be difficult to fashion a definition that would apply in all cases. The Supreme Court left the definition of this essential term to other courts in future cases.

The court in this case concluded that the ministerial exception applied to a non-ordained guidance counselor in a Catholic parochial school, noting that “[a]s a general rule, if the employee’s primary duties consist of teaching, spreading the faith, church governance, supervision of a religious order, or supervision or participation in religious ritual and worship, he or she should be considered ‘clergy,’” quoting Rayburn v. General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, 772 F.2d 1164 (4th Cir. 1985). This is a broad definition extending beyond formal ordained status.

The court stressed that “the purpose of the ministerial exception is to allow religious employers the freedom to hire and fire those with the ability to shape the practice of their faith.”

One other aspect of this case merits attention. The court placed great weight on the plaintiff’s job description. The importance of job descriptions in ministerial exception cases cannot be understated.

Churches should review job descriptions, especially for non-ordained staff, to see if employees who might meet the definition of “minister” for purposes of the ministerial exception have job descriptions that describe and stress their religious functions.

Caution. Before dismissing someone for violating the church’s moral teachings, leaders should answer the five questions found in the “Discrimination Based on Religion or Morals” section of the Legal Library. This section also includes tips and case studies pertinent to this topic.

Starkey v. Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Indianapolis, Inc., 553 F. Supp. 3d 616 (S.D. Ind. 2021)