Does your church use Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised as its parliamentary authority, either by a specific reference in the church bylaws or by common usage? If so, it is important for you to be familiar with the key provisions in the new and revised 12th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised to ensure that your board and membership meetings are being conducted consistently with your parliamentary authority.

In late 2020, the new and fully revised 12th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised was released. It replaces all earlier editions, including the most recent 11th edition that was published in 2010.

The preface to the new edition explains the need for a revision as follows:

This Twelfth Edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised clarifies, modifies, and expands upon the rules in previous editions, as situations occurring in assemblies point to a need for more fully developed rules to go by in particular cases.

This new edition contains more than 89 substantive changes in parliamentary procedure. It is important for church leaders to be aware of this development since most church bylaws identify Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised as the official parliamentary authority in the conduct of membership meetings. The preface to the 12th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised states:

This Twelfth Edition supersedes all previous editions and is intended automatically to become the parliamentary authority in organizations whose bylaws prescribe “Robert’s Rules of Order,” “Robert’s Rules of Order Revised,” “Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised,” or “the current edition of” any of these titles, or the like, without specifying a particular edition. If the bylaws specifically identify one of the 11 previous editions of the work as parliamentary authority, the bylaws should be amended to prescribe “the current edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised.”

As a result, any church that has identified Robert’s Rules of Order or Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised in its governing document will be bound by the rules contained in the 12th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised. It is for this reason that church leaders should be familiar with the new text. This article will explain the 17 most important changes that are relevant to church meetings and practice.

Example. A church’s bylaws state that “the parliamentary authority for all church business meetings shall be Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised (7th edition 1970). The church must use this edition as it’s parliamentary authority. The church should amend its bylaws to define its parliamentary authority as “the current edition” of Robert’s Rules of Order or Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised.

Example. A church’s bylaws state that “the parliamentary authority for all church business meetings shall be Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised.” The preface to the 12th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised states that the 12th edition “is intended automatically to become the parliamentary authority in organizations whose bylaws prescribe ‘Robert’s Rules of Order,’ ‘Robert’s Rules of Order Revised,’ ‘Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised,’ or ‘the current edition of’ any of these titles . . . without specifying a particular edition.”

Note. Each example that follows assumes that a church has adopted the current edition of Roberts Rules of Order Newly Revised as its parliamentary authority.

1. Rearranges the rules that apply to the motion to Lay on the Table

One of the most misunderstood motions in parliamentary law is the motion to Lay on the Table. It is common during the consideration of a motion for someone to blurt out “Table” or “Table it,” as a way to kill any further discussion of a pending motion. But there is no such motion in Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised and so it is an improper motion. Here are the key points to note, as set forth in section 17 of the 12th edition :

- Section 17.2 states that “in ordinary assemblies, the motion to Lay on the Table is not in order if the evident intent is to kill or avoid dealing with a measure.”

- The motion to Lay on the Table does not kill consideration of a motion, but rather enables the assembly to lay the pending question aside temporarily when something else of immediate urgency has arisen or when something else needs to be addressed before consideration of the pending question is resolved, with the understanding that consideration of the pending motion is resumed by vote of the majority.

- Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised does recognize a motion to Postpone Indefinitely which is designed to allow members to permanently kill a pending motion.

Example. During debate on a motion during a church business meeting, a member shouts “I move that we table the motion” with the intent to kill any further discussion of the pending motion. The chair should inform the member that there is no motion to table in Roberts Rules of Order, but that if his intent is to kill further consideration of the motion, the way to do so is by a motion to Postpone Indefinitely. Such a motion requires a second, is debatable, is not amendable, cannot interrupt a pending motion, and requires a majority vote to pass.

Example. A church convenes its annual business meeting at 10 a.m. on a Saturday morning in the sanctuary. The meeting takes longer than expected. At 1 p.m., the members are engaged in consideration of an important motion. Several members are concerned that the meeting may last for at least a few more hours. A member moves to Lay on the Table the pending motion so that members can break for lunch. Following a one-hour lunch break, the meeting resumes, and a motion is offered to take the motion from the table. Such a motion requires a majority vote.

2. Rules pertaining to the office of vice-president

Section 47:23-31 of the 12th edition consolidates and clarifies the rules pertaining to the office of vice-president. In prior editions of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised, these rules were scattered throughout the text. Here are the main provisions:

- In the absence of the president, or when for any reason the president vacates the chair, the vice-president serves in his or her stead.

- When a vice-president is presiding over a meeting, he or she is addressed as “Mr. President” or Madam President,” unless confusion might result, for example, when the president is also on the platform. In which case, the form “Mr. Vice President” or “Madam Vice President” may be used.

- If the bylaws provide that the president shall appoint all committees, this power does not transfer to a vice-president occupying the chair, even when the president is absent.

- The president and vice-president may have occasion to make reports in connection with their duties prescribed in the bylaws. If the president has prepared a report but cannot attend a meeting at which it is to be presented, the vice-president should present it. But the vice-president cannot modify the president’s report, or substitute a different one for it, simply because the president is absent.

- In the case of the president’s resignation, death, or removal, the vice-president automatically becomes president for the remainder of the term, unless the bylaws expressly provided otherwise for filling a vacancy in the office of president.

- Although in many cases the outgoing vice-president will be the logical nominee for president for the next term, the church has the freedom to make its own choice and to elect the most promising candidate at that time, unless stated otherwise in the bylaws.

3. Executive session

An executive session in general parliamentary usage has come to mean any meeting of a deliberative assembly, or a portion of a meeting, at which the proceedings are secret. As a general rule, anything that occurs in executive session may not be divulged to nonmembers (except any entitled to attend). However, section 9:26-27 of the 12th edition provides the following clarification:

[A]ction taken, as distinct from that which was said in debate, may be divulged to the extent—and only to the extent—necessary to carry it out. . . . If an assembly wishes to further lift the secrecy of action taken in an executive session, it may adopt a motion to do so, which is a motion to Amend Something Previously Adopted.

4. Electronic voting

Section 45:42 of the 12th edition clarifies that the use of electronic devices, such as voting keypads, can fulfill a requirement that voting be by ballot:

[The use of such devices to conduct voting] may be directed by a special rule of order or convention standing rule. . . . Members must be able to indicate their choices without revealing how they have voted. If the devices are to be used for an election, provision must be made to allow voters to cast write-in votes. If the devices are to be used to conduct voting on several questions or several independent offices simultaneously, then they must be programmed to allow the number of votes cast for purposes of computing the majority to be tallied independently for each question or office.

5. Making board minutes available to others

Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised has long provided that a record of a board’s proceedings is kept by the secretary, and only members of the board have the right to examine the minute book kept by the secretary unless the board orders otherwise. The board can order that any specified persons, including, for example, all members of the assembly, be permitted to view or be furnished copies of board minutes.

Section 49:19 of the 12th edition further provides:

Whether or not board minutes are protected by the secrecy of an executive session, the assembly of the society can adopt a motion granting such permission, or can order that the board’s minutes be produced and read at a meeting of the assembly, by a two-thirds vote, the vote of the majority of the entire membership of the assembly, or a majority vote if previous notice has been given.

Example. During the annual business meeting of a church, a motion is offered to require the minutes of the board of deacons to be read at each annual business meeting of the church. The motion receives a vote of 60 percent. While not entirely clear, section 49:19 seems to require a two-thirds vote for the board minutes to be read at a meeting of the assembly, and as a result the motion is lost.

Example. Same facts as the previous example except that valid notice of the meeting was provided to the membership pursuant to the church bylaws. Section 49:19 specifies that the church can by majority vote grant the motion if previous notice has been given.

Tip. A church not wanting a broad distribution of board minutes has the option of amending the church bylaws to restrict distribution of board minutes solely to members of the board.

6. Terms of office

Section 56:27 of the 12th edition contains the following helpful clarification regarding terms of office:

When the bylaws specify the number of years in a term of office, it is understood that the actual term may be more or less than a whole number of calendar years, owing to permissible variation in the dates on which successive elections are scheduled.

Section 57:27 illustrates this clarification with the following example:

Example. The bylaws provide that the annual meeting for the election of officers shall take place “in October or November,” that their terms of office shall begin “at the close of the annual meeting,” and that they shall serve for a term of “one-year and until their successors are elected.” If the annual meeting is held on October 20 of one year and on November 1 of the next, the officers elected at the second meeting take office immediately upon the adjournment of that meeting—and the previous officers remain in office until that time—even though this represents a term of office longer than one calendar year.

7. A bylaw revision must be prepared by a committee authorized to draft it

Section 57:5 of the 12th edition specifies that “consideration of a revision of the bylaws is in order only when prepared by a committee that has been properly authorized to draft it, either by the membership or by an executive board that has the power to refer such matters to a committee.”

This provision, and many others described in this article, illustrate a fundamental flaw that has plagued the last several editions of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised. Henry Robert’s purpose in compiling his original Robert’s Rules of Order in 1876 is described in the preface as follows:

There appears to be much needed a work on parliamentary law . . . adapted, in its details, to the use of ordinary societies. Such a work should give, not only the methods of organizing and conducting the meetings, the duties of the officers and the names of the ordinary motions, but in addition, should state in a systematic manner, in reference to each motion, its object and effect; whether it can be amended or debated; if debatable, the extent to which it opens the main question to debate; the circumstances under which it can be made, and what other motions can be made while it is pending.

That is, Robert’s Rules of Order was written to provide a body of rules to assist organizations in conducting meetings with order, decorum, consistency, and efficiency. The original work was devoted entirely to an explanation of these rules. Its table of contents included two parts: rules of order and conduct of business.

But subsequent editions of Robert’s Rules of Order and Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised have introduced several new subjects pertaining to matters of church governance and administration rather than “rules of order.” These include the following:

- The selection and duties of the vice-president, secretary, and treasurer; honorary officers; appointed officers; and filling vacancies.

- The content and form of minutes of board and member meetings.

- The selection, authority, and removal of board members; ex officio board members; the appointment of committees; and the conduct of business in boards and committees.

- Church bylaws almost always define a quorum for both board and membership meetings, a quorum being the minimum number of members present in order for business to be transacted. If a church’s bylaws fail to designate a quorum, then the state nonprofit corporation law under which the church is incorporated will define a quorum. It is almost inconceivable that Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised will ever be the authority that defines a quorum in meetings of a church’s board or members.

- The content and composition of bylaws; drafting of bylaws; appointment of a bylaws committee; articles to be included in bylaws (Article I: Name, Article II: Object, Article III: Members, Article IV: Officers, Article V: Meetings, Article VI: Board of Directors, Article VII: Committees, Article VIII: Parliamentary Authority, Article IX: Amendments); a sample set of bylaws; principles of interpretation; amendment of bylaws; giving members notice of bylaw amendments; and when bylaw amendments take effect.

- The discipline and punishment of members; removal of officers for dereliction of duties; investigations; trials; rights of the accused; and fair procedures.

These subjects address matters of church governance and administration that are addressed in a church’s bylaws or, in some cases, in the nonprofit corporation law under which a church is incorporated. They have nothing to do with parliamentary procedure and therefore their inclusion in Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised not only is inappropriate, but it creates needless confusion due to the inevitable conflicts that will arise between a church’s bylaws and its parliamentary authority.

Note the following two rules of construction:

Rule 1. A church’s bylaws always take precedence over conflicting provisions in Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised, since bylaws are a higher legal authority and are superseded only by a church’s charter (articles of incorporation) and, in some cases, by a church’s constitution and denominational rules.

Rule 2. Any provision in Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised that does not pertain to parliamentary procedure exceeds the scope and purpose of Robert’s Rules and is superseded by conflicting provisions in a church’s charter, constitution, or bylaws.

These rules are illustrated by the following examples.

Example. A church’s bylaws specify that the quorum for annual membership meetings is 20 percent of all members. State nonprofit corporation law under which the church is incorporated specifies that a quorum is 10 percent of members. Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised specifies that the quorum in church meetings “consists of those who attend.” This is a perfect example of the impropriety of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised addressing issues of governance. The definition of a quorum in Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised is irrelevant. The operative quorum is the 20 percent specified in the church’s bylaws.

Example. Section 56 in the 12th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised states that the sequence of articles in an organization’s bylaws should be as follows: Article I: Name, Article II: Object, Article III: Members, Article IV: Officers, Article V: Meetings, Article VI: Board of Directors, Article VII: Committees, Article VIII: Parliamentary Authority, Article IX: Amendments. A church’s bylaws include several articles not referenced in Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised. Does this mean that the bylaws need to be amended to delete the additional articles in order to correspond to Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised? Of course not. Remember, the bylaws control over conflicting provisions in Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised, and this is especially true for those provisions in Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised having nothing to do with parliamentary procedure.

Why does a manual on parliamentary procedure address the discipline and removal of officers? Not only does this make no sense when this topic is covered under both corporation law (both nonprofit and for-profit) and an entity’s bylaws or articles of incorporation, but it will lead to needless confusion as to the controlling rule (articles, bylaws, nonprofit corporation law, or parliamentary authority).

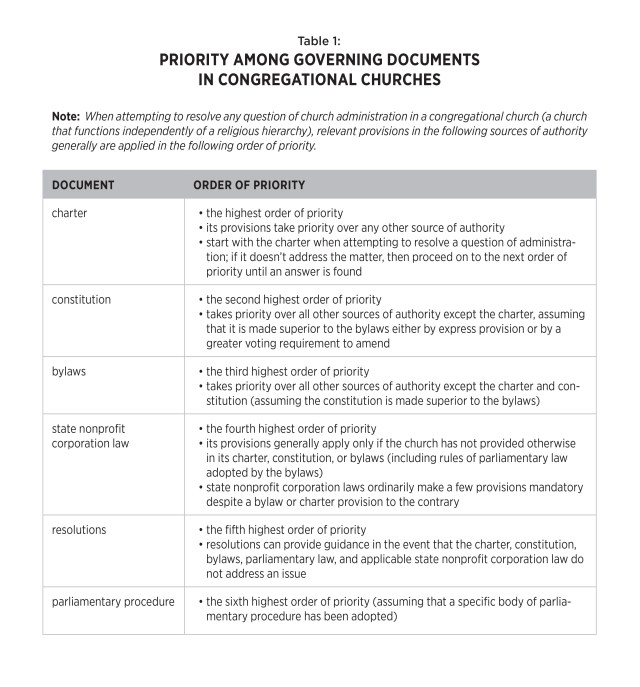

How should church leaders determine the governing document when there is a conflict in the various sources of authority? Consider the previous example of a church that is trying to determine the quorum requirement for its annual business meeting. Its bylaws specify 20 percent, the applicable nonprofit corporation statute says 10 percent, and Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised says “those who attend.” It is easy to see how these conflicts can lead to needless confusion and uncertainty.

Some may challenge the legality of a meeting based on noncompliance with one or more of these sources of authority. Table 1 provides church leaders with a tool for determining the ranking of various sources of authority in “congregational” churches (those that function independently of a religious hierarchy). Start at the top, and go down the list until you find the highest authority to address a particular question.

This process will guide you to the controlling authority. In the church quorum example, the highest ranked authority would be the church’s bylaws, meaning that the applicable quorum is 20 percent of all members. So, a meeting at which 12 percent of members attend would not satisfy the quorum requirement even though it would satisfy the quorum definition under the state nonprofit corporation law and Robert’s Rules.

Caution. According to Table 1, the revised section in Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised pertaining to the discipline of officers would have no relevance or application to the discipline of officers in a church that is incorporated under the Model Nonprofit Corporation Act or whose charter, constitution, or bylaws address the discipline of officers, making conflicting provisions in Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised inapplicable and irrelevant.

8. Appendix containing sample rules for electronic meetings

The 12th edition includes a 15-page Appendix that provides rules to follow when conducting electronic meetings. Separate rules, and sample bylaw amendments, are provided for the following categories:

A. Full-featured internet meeting services that integrate audio, video, text, and voting capabilities.

B. Telephone meetings, with internet services for conducting secret votes and sharing documents.

C. A speakerphone in the meeting room to allow members who are not physically present to participate by telephone.

D. Telephone meetings without internet support and without any central meeting room.

To illustrate, the following sample bylaw amendment is provided for category “A”:

Meetings held electronically. Except as otherwise provided in these bylaws, meetings of the Board shall be conducted through use of Internet meeting services designated by the President that support anonymous voting and support visible displays identifying those participating, identifying those seeking recognition to speak, showing (or permitting the retrieval of) the text of pending motions, and showing the results of votes. These electronic meetings of the Board shall be subject to all rules adopted by the Board, or by the Society, to govern them, which may include any reasonable limitations on, and requirements for, Board members’ participation. Any such rules adopted by the Board shall supersede any conflicting roles in the parliamentary authority, but may not otherwise conflict with or alter any rules or decision of the Society. An anonymous vote conducted through the designated Internet meeting service shall be deemed a ballot vote, fulfilling any requirement in the bylaws or rules that a vote be conducted by ballot.

Note. This proposed bylaw provision is inadequate in some respects and should not be relied upon without the advice of legal counsel. Further, it is superseded by any provisions in a church’s bylaws or applicable nonprofit corporation law pertaining to electronic voting.

The 12th edition includes sample rules that can be adopted to assist with the conduct of electronic meetings. These rules, for category “A” scenarios, include the following subjects:

- Login information

- Login time

- Signing in and out

- Quorum calls

- Technical requirements and malfunctions

- Forced disconnections

- Assignment of the floor

- Interrupting a member

- Motions submitted in writing

- Display of motions

- Voting

- Video display

9. Excluding nonmembers from a meeting without going into executive session

“Executive session” refers to a meeting, or part of a meeting, of a board or other deliberative assembly that is conducted in secret with only members and invited guests being present.

Section 9:25 of the 12th edition contains a new provision allowing a board to exclude nonmembers from a meeting without going into executive session. It states:

[I]n the case of a board or committee meeting being held in executive session, all persons—whether or not they are members of the organization–who are not members of the board or committee (and who are not otherwise specifically invited or entitled to attend) are excluded from the meeting. When it is desired to similarly restrict attendance at a particular meeting without imposing (or to remove a previously imposed restriction on attendance), this may also be done by majority vote.

Example. A church board is discussing the discipline of a member during a scheduled meeting of the board. Two church members (who are not board members) show up and request permission to attend. The board can exclude these two members from attending either by transitioning into executive session or by voting to exclude them (majority vote). Executive session is appropriate if confidential matters will be discussed. The second option is appropriate if there is no confidential information to protect.

Example. A church member begins attending board meetings insisting that it is his right to do so. The board can exclude this member from attending either by transitioning into executive session, or by voting to exclude him (majority vote). Executive session is appropriate if confidential matters will be discussed. The second option is appropriate if there is no confidential information to protect.

10. Ratification of actions taken without a valid meeting

Ratification means the formal approval of a previously unauthorized act. For example, a church board votes to sell a home that was donated to the church. The church’s bylaws state that only the members in a membership meeting have the authority to sell church property. While the sale was unauthorized, it can be ratified by the membership in a church business meeting.

Section 10:54 in the 12th edition adds the following new information regarding ratification:

The motion to ratify (also called approve or confirm) . . . is used to confirm or make valid an action already taken that cannot become valid until approved by the assembly. Cases where the procedure of ratification is applicable include . . . action taken by officers, committees, delegates, subordinate bodies, or staff in excess of their instructions or authority including action to carry out decisions made without a valid meeting, such as by approval obtained separately from all board members or at an electronic meeting of a body for which such meetings are not authorized.

Example. A church conducted its annual business meeting by means of a virtual internet connection. Church leaders later discovered that its bylaws did not authorize electronic meetings. The unauthorized actions taken at this meeting can be ratified in a subsequent business meeting of the members.

11. Changing one’s ballot

Section 45 of the previous 11th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised specified that a member has a right to change his vote “up to the time the result is announced; after that, you can make the change only by the unanimous consent of the assembly requested and granted, without debate, immediately following the chair’s announcement of the results of the vote.”

Section 45:8 of the new 12th edition modifies this language as follows:

Except when the vote has been taken by ballot (or some other method that provides secrecy), a member has a right to change his vote up to the time the vote is announced but afterward can make the change only by the unanimous consent of the assembly requested and granted, without debate, immediately following the chair’s announcement of the results of the vote.

According to this language, the right of a member to change a vote does not apply when the vote is taken by ballot or some other method providing secrecy.

Example. A church conducts an election for two officers by ballot, during its annual business meeting. Following the chair’s announcement of the vote, a member rises and requests permission to change her vote. The chair should rule that this request is out of order since under the newly revised 12th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised the right of a member to change a vote does not apply when the vote is taken by ballot or some other method providing secrecy.

12. Secrecy of ballot votes

Section 45 of the previous 11th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised specified:

When a vote is to be taken, or has been taken, by ballot, whether or not the bylaws require that form of voting, no motion is in order that would force the disclosure of a member’s vote our views on the matter.

Section 45 of the new 12th edition modifies this language as follows:

When the bylaws require a vote to be taken by ballot, this requirement cannot be suspended—even by unanimous vote—so as to take the vote by a non-secret method.

Example. During a church business meeting, the election of a pastor is on the agenda. The church board presents one candidate for consideration. The chair, in an effort to expedite business, asks for unanimous approval to vote by a show of hands even though the church’s bylaws require voting by ballot. According to the new 12th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised, the bylaw requirement for voting by ballot cannot be disregarded even by unanimous vote.

13. “Secret ballots”

Section 45:18 of the new 12th edition clarifies that voting by ballot is synonymous with voting by secret ballot. This was never clarified in previous editions of Robert’s Rules.

14. Balloting by mail

Section 45 of the previous 11th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised specified that elections by ballot can be conducted by mail if the bylaws so provide. However, “unless repeated balloting by mail is feasible in cases where no candidate attains a majority, the bylaws should authorize the use of some form of preferential voting or should provide that a plurality shout aloud.”

The new 12th edition adds that the bylaws should provide for a method of election if there is a tie.

15. Ex officio officers

Section 45 of the previous 11th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised specified that an ex officio board member who is “under the authority” of the organization in the sense that he or she is a member, employee, or elected or appointed officer, is treated the same as any other director. An ex officio member has both the benefits and obligations of being a director.

However, an ex officio director who is not under the authority of the organization “should not be counted in determining the number required for a quorum or whether a quorum is present at a meeting.” Further, “whenever an ex officio board member is also ex officio an officer of the board, he of course has the obligation to serve as a regular working member.”

Section 49:8 of the 12th edition provides the following clarification:

If the ex officio member is not under the authority of the society, he has all the privileges of board membership, including the right to make motions and to vote, but none of the obligations. . . . The latter class of ex officio board members, who [have] no obligation to participate, [are] not counted in determining the number required for a quorum or whether a quorum is present at the meeting. Whenever an ex officio board member is also ex officio an officer of the board, he of course has the obligation to serve as a regular working member and is therefore counted in the quorum.

Example. A church classifies a former board member who had served on the board for 30 years as an ex officio member of the board. While this director may vote and make motions, he or she is not required to participate in any board meetings and in fact rarely does so. Since this ex officio member has no obligation to participate in board meetings, he or she is not counted in determining the number required for a quorum or whether a quorum is present at a meeting.

Example. A church designates an ex officio member as an ex officio officer. The new 12th edition of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised provides that “whenever an ex officio board member is also ex officio an officer of the board, he of course has the obligation to serve as a regular working member and is therefore counted in the quorum.”

16. Correct procedure for “receiving” a report

Previous editions of Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised specified that reports of officers, boards, and committees were “received” when read: “When the assembly hears the report thus read or orally rendered, it receives the report.”

In other words, the person reading the report presents it, while the listeners receive it. As a result, it is incorrect parliamentary practice for a motion to be made at a board or membership meeting to “receive” a report after it is presented, since the act of presenting it constitutes reception by the hearers.

Section 51:28 of the new 12th edition goes a step further and states that a motion to receive a report is out of order:

A common error is to move that a report “received” after it has been read—apparently on the supposition that such a motion is necessary in order for the report to be taken under consideration or to be recorded as having been made. In fact, this motion is meaningless and therefore not in order, since the report has already been received.

Example. During a church business meeting, the secretary presents her report and a motion is made to “receive” the report. The chair should rule this motion out of order since the presentation of the report constitutes its receipt. The new 12th edition states: “[T]his motion is meaningless and therefore not in order, since the report has already been received.”

The 12 edition states that motions to adopt or accept the report of an officer or committee are synonymous, and signify that the entire report becomes “the act or statement of the assembly.” Such motions are common in church board and membership meetings.

To illustrate, it is common for motions to be made and passed to accept a treasurer’s report or the minutes of the previous meeting. It is important to understand, however, that such motions have the effect of “the assembly’s endorsing every word of the report, including the indicated facts and reasoning, as its own statement.”

This may not be a problem in some, or even most, cases. For example, a board may want to formally adopt the minutes of each meeting, since they reflect the actions of the board itself. But there can be situations in which it would be more appropriate for a board or assembly to merely receive a report (by having it presented), and then referring it to the secretary of the board.

In some organizations, the treasurer’s reports to the board of directors are not accepted or adopted (so long as they contain no specific recommendations for action).

Instead, the chairperson requests the secretary to file these reports without action. At the end of the fiscal year, the board adopts a motion to accept the report of the CPA firm that audits the organization’s books.

This has the effect of relieving the treasurer of any personal culpability for his or her reports (excepting fraudulent or illegal activity). It also may minimize the board’s culpability that might otherwise exist if it adopted or accepted each report of its treasurer. The organization itself, at its annual business meeting, also adopts or accepts by motion the CPA’s audit report.

The 12th edition states:

[N]o action of acceptance by the assembly is required, or proper, on a financial report of the treasurer unless it is a sufficient importance, as an annual report, to be referred to auditors. In the latter case it is the auditors’ report which the assembly accepts. The treasurer’s financial report should therefore be prepared long enough in advance for the audit to be completed before the report is made at the meeting of the society.

Some reports of officers or committees contain one or more recommendations for action. In such cases, it is appropriate and necessary for a motion to adopt the recommendation. Usually, such a motion is made by the person presenting the report. But again, many reports made by officers and committees to a board or assembly are for informational purposes and contain no recommendations or motions. There is no need for a motion to accept or adopt such a report, since it is for informational purposes only and contains no recommended action.

The appropriate response by the chairperson to the reading of such reports is to refer them to the secretary for filing with the minutes, without any formal motion. In this regard, Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised states: “Apart from filing such a report . . . no action on it is necessary and usually none should be taken.”

Example. At a regularly scheduled meeting of a church board, a committee member reads a report that contains no proposed actions. It would be appropriate for the chairperson to thank the committee and request that the report be placed on file, and then move to the next item of business. A motion to accept or adopt the report is not necessary, since it is informational.

17. Notice of proposed bylaw amendments

The 12th edition states:

Where assemblies meet regularly only once a year, instead of requiring amendments to be submitted at the previous annual meeting, the bylaws should provide for both notice and copies of the proposed amendments to be sent to the member delegates . . . a specified minimum number of days in advance (emphasis added).

The previous 11th Edition of Robert’s Rules stated that “the bylaws should provide for both notice and copies of the proposed amendment to be sent to the member delegates,” but did not recommend that the bylaws be amended to include such a provision.

Richard R. Hammar is an attorney, CPA and author specializing in legal and tax issues for churches and clergy.